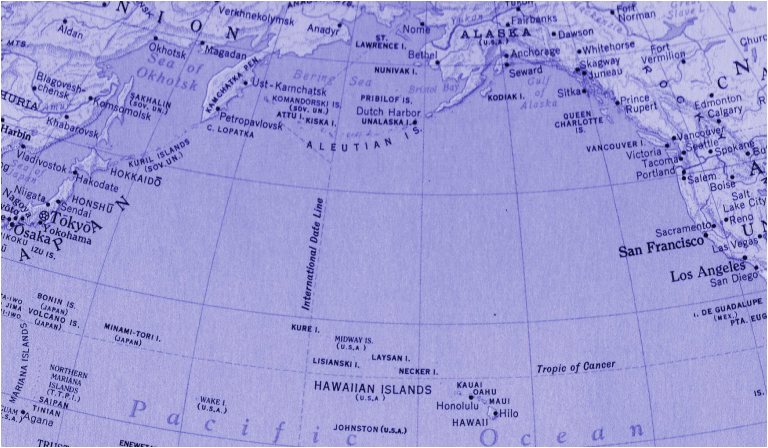

The map came from the Rand-McNally Universal World Atlas, new revised edition. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1988, page 8. Incidentally, this map is probably very like the only West Coast maps that were available to the RCAF when they sent their fliers north to Alaska. Pilots found their way up the BC coast to Alaska with school maps. Ironically, the Japanese, too, were labouring under the same limitations. (See qoute below)

The Pacific Basin

This map shows the north Pacific Ocean and the countries that rim it. No one is sure exactly what Japan's intentions were with respect to North America. But, judging from their attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941, they were very worried that United States naval power could interfere with their own imperial intentions in the Pacific. [As a note of interest: the distance between Tokyo and San Francisco is 5,133 miles or 8,260 kilometers.]

Japan's Admiral Yamamoto, a great believer in the power of the aircraft carrier as the tool to extend Japan's sphere of influence, decided that he would have to reduce the American fleet and, at the same time, seize secure toe-holds around the Pacific Basin. He, with difficulty, managed to sell the idea to Japanese policy-makers and, on June 3, 1942, six months after they attacked Pearl Harbor, two aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers and three destroyers launched an attack on the American naval base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands. The plan was to soften Dutch Harbor and then land a garrison of troops on the neighbouring island of Adak, That the Americans met his attack with such strength surprised him. He had to settle for installations on Attu and Kiska Islands.

Rear Admiral L.O. Colbert, director of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey was quoted as saying: "In all the Japanese equipment taken during and after the war, no one ever found a map or chart of Alaska or the Aleutian Islands. If they had had any, they would not have moved into Kiska, one of the poorest excuses for a naval base they could have found." Thanks to Bo Jensen for finding this quotation.

In those same days in early June, 1942, Yamamoto was racing his main battle fleet toward Midway Island where he expected to complete the destruction of the American fleet, most especially their aircraft carriers which he missed at Pearl Harbor. The outcome of that battle, known as the Battle of Midway (because it occurred near Midway Island), proved to be a crushing defeat for Yamamoto. He took staggering losses.

So it is not clear why he continued to press the attack in the Aleutians. Had he kept these ships in his main fleet, the Battle of Midway would very likely have ended in his favour. For a very interesting exploration of this theme, see Alistair Horne's HUBRIS The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth Century. He noted this: "Using strictly mathematical reasoning, Yamamoto, with his 4:3 ratio in carriers manned by crack crews, and his extensive backup of battleships and cruisers should have won at Midway. In fact, however, he had lost before the engagement began. Instead of concentrating his forces on the main objective, as Napoleon would have done on land, Yamamoto with his ambitiously complex plans dispersed them on trivial targets such as the strategically worthless Aleutians. The two light carriers Yamamoto dispatched there could well have tipped the balance at Midway, and once Midway had been taken or neutralized, the Aleutians would have fallen into his pocket for the asking." (p. 275)

There are, at least, three possible explanations:

- he needed his toe-hold to prevent the Americans from having it

- he planned to use the Aleutian Islands as the base from which he could mount an attack against the U.S. West Coast

- he needed to weaken his enemy by causing him to divert resources.

The "Needing the toe-hold" theory gets some support when we consider that the time (Spring, 1942) that the Japanese high command was considering what to do next after Pearl Harbor, a small group of American bombers, under the command of General Doolittle, attacked Tokyo. The material damage done was not great but the symbolic damage shook the Japanese command. They could not figure out where the bombers had come from. A plausible explanation was that they had flown from the Aleutian Islands. A less plausible (in their minds) explanation was that they had taken off from an aircraft carrier. In fact, they had taken off from the U.S.S. Hornet which secretly had steamed to a position just 600 miles off the coast of Japan. They struck on April 14, 1942.

If Yamamoto only wanted to divert North American resources, he was very successful indeed. At the "investment" (a coldly military perspective) of only a few thousand men, the Japanese successfully tied up nearly half a million U.S. and Canadian troops for a year and a half. Both the United States and Canada formed a cooperative alliance. A hugely costly highway was built through Canada which connected Alaska with the continental United States. Four Canadian Air Force Squadrons (two bomber and two fighter squadrons) were created and deployed in Alaska, Kodiak Island and Umnak Island, to fight alongside the United States Army's 11th Air Force. A lot of airbases were built in remote areas. It would require an invading force of 20,000 U.S. and some 5,000 Canadian Infantrymen to finally persuade the Japanese that it was time to withdraw.

Nevertheless, his "investment" cost him, and his country, the war.

According to the resident expert on the Battle of Midway in the Japanese War History Office, Commander Tsunoto, as quoted by Jack Lord, noted historical fiction author, who interviewed him in the late 1960's, Japan's two dominant Naval Command sections were at odds with each other. One side (headed by Admiral Yamamoto) wanted to finish off the American fleet at Midway. The other, perhaps spooked (my speculation) by the Doolittle raid, wanted to establish a protective Japanese toe-hold in the Aleutians. Yamamoto, in an attempt to placate the other side, agreed to do both.

(See more on this issue in Stan Cohen's Volume II The Forgotten War where he cites the Jack Lord interview with Commander Tsunoto on page vii.)

It is clear that the stakes were high and the contest was engaged in earnest by both the North American and Japanese sides.

While we might think now that any thought of invading North America was pure folly, we need to remind ourselves as to just how unready Canada was to defend herself against invasion of the west coast. General Andrew McNaughton, Chief of General Staff of the Canadian military, submitted a report to the Government of Canada (Prime Minister Bennett) describing the military's state of readiness. His report, entitled The Defence of Canada, dated January, 1935, made these observations about Canada's defensive weapons on the West Coast:

"Except as regards rifles and rifle ammunition, partial stocks of which were inherited from the Great War-there are none. As regards equipment, the situation is almost equally serious, and to exemplify it I select a few items from the long lists of deficiencies on file at National Defence Headquarters:

This is from the book Six Years of War, the Official History of the Canadian Army, Department of National Defence. (page 6)

So, it is clear, RCAF No. 111 (F) Squadron was a part of Canada's desperate attempt to get our defences back in our own control.

Japan's Admiral Yamamoto, a great believer in the power of the aircraft carrier as the tool to extend Japan's sphere of influence, decided that he would have to reduce the American fleet and, at the same time, seize secure toe-holds around the Pacific Basin. He, with difficulty, managed to sell the idea to Japanese policy-makers and, on June 3, 1942, six months after they attacked Pearl Harbor, two aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers and three destroyers launched an attack on the American naval base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands. The plan was to soften Dutch Harbor and then land a garrison of troops on the neighbouring island of Adak, That the Americans met his attack with such strength surprised him. He had to settle for installations on Attu and Kiska Islands.

Rear Admiral L.O. Colbert, director of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey was quoted as saying: "In all the Japanese equipment taken during and after the war, no one ever found a map or chart of Alaska or the Aleutian Islands. If they had had any, they would not have moved into Kiska, one of the poorest excuses for a naval base they could have found." Thanks to Bo Jensen for finding this quotation.

In those same days in early June, 1942, Yamamoto was racing his main battle fleet toward Midway Island where he expected to complete the destruction of the American fleet, most especially their aircraft carriers which he missed at Pearl Harbor. The outcome of that battle, known as the Battle of Midway (because it occurred near Midway Island), proved to be a crushing defeat for Yamamoto. He took staggering losses.

So it is not clear why he continued to press the attack in the Aleutians. Had he kept these ships in his main fleet, the Battle of Midway would very likely have ended in his favour. For a very interesting exploration of this theme, see Alistair Horne's HUBRIS The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth Century. He noted this: "Using strictly mathematical reasoning, Yamamoto, with his 4:3 ratio in carriers manned by crack crews, and his extensive backup of battleships and cruisers should have won at Midway. In fact, however, he had lost before the engagement began. Instead of concentrating his forces on the main objective, as Napoleon would have done on land, Yamamoto with his ambitiously complex plans dispersed them on trivial targets such as the strategically worthless Aleutians. The two light carriers Yamamoto dispatched there could well have tipped the balance at Midway, and once Midway had been taken or neutralized, the Aleutians would have fallen into his pocket for the asking." (p. 275)

There are, at least, three possible explanations:

- he needed his toe-hold to prevent the Americans from having it

- he planned to use the Aleutian Islands as the base from which he could mount an attack against the U.S. West Coast

- he needed to weaken his enemy by causing him to divert resources.

The "Needing the toe-hold" theory gets some support when we consider that the time (Spring, 1942) that the Japanese high command was considering what to do next after Pearl Harbor, a small group of American bombers, under the command of General Doolittle, attacked Tokyo. The material damage done was not great but the symbolic damage shook the Japanese command. They could not figure out where the bombers had come from. A plausible explanation was that they had flown from the Aleutian Islands. A less plausible (in their minds) explanation was that they had taken off from an aircraft carrier. In fact, they had taken off from the U.S.S. Hornet which secretly had steamed to a position just 600 miles off the coast of Japan. They struck on April 14, 1942.

If Yamamoto only wanted to divert North American resources, he was very successful indeed. At the "investment" (a coldly military perspective) of only a few thousand men, the Japanese successfully tied up nearly half a million U.S. and Canadian troops for a year and a half. Both the United States and Canada formed a cooperative alliance. A hugely costly highway was built through Canada which connected Alaska with the continental United States. Four Canadian Air Force Squadrons (two bomber and two fighter squadrons) were created and deployed in Alaska, Kodiak Island and Umnak Island, to fight alongside the United States Army's 11th Air Force. A lot of airbases were built in remote areas. It would require an invading force of 20,000 U.S. and some 5,000 Canadian Infantrymen to finally persuade the Japanese that it was time to withdraw.

Nevertheless, his "investment" cost him, and his country, the war.

According to the resident expert on the Battle of Midway in the Japanese War History Office, Commander Tsunoto, as quoted by Jack Lord, noted historical fiction author, who interviewed him in the late 1960's, Japan's two dominant Naval Command sections were at odds with each other. One side (headed by Admiral Yamamoto) wanted to finish off the American fleet at Midway. The other, perhaps spooked (my speculation) by the Doolittle raid, wanted to establish a protective Japanese toe-hold in the Aleutians. Yamamoto, in an attempt to placate the other side, agreed to do both.

(See more on this issue in Stan Cohen's Volume II The Forgotten War where he cites the Jack Lord interview with Commander Tsunoto on page vii.)

It is clear that the stakes were high and the contest was engaged in earnest by both the North American and Japanese sides.

While we might think now that any thought of invading North America was pure folly, we need to remind ourselves as to just how unready Canada was to defend herself against invasion of the west coast. General Andrew McNaughton, Chief of General Staff of the Canadian military, submitted a report to the Government of Canada (Prime Minister Bennett) describing the military's state of readiness. His report, entitled The Defence of Canada, dated January, 1935, made these observations about Canada's defensive weapons on the West Coast:

"Except as regards rifles and rifle ammunition, partial stocks of which were inherited from the Great War-there are none. As regards equipment, the situation is almost equally serious, and to exemplify it I select a few items from the long lists of deficiencies on file at National Defence Headquarters:

- There is not a single modern anti-aircraft gun of any sort in Canada.

- The stocks of field gun ammunition on hand represent 90 minutes' fire at normal rates for the field guns inherited from the Great War and which are now obsolescent.

- The coast defence armament is obsolescent and, in some cases, defective in that a number of the major guns are not expected to be able to fire more than a dozen or so rounds. To keep some defence value in these guns, which are situated on the Pacific coast, we have not dared for some years to indulge in any practice firing.

- About the only article of which stocks are held is harness, and this is practically useless. The composition of a modern land force will include very little horsed transport.

- There are only 25 aircraft of service type in Canada, all of which are obsolescent except for training purposes; of these, 15 were purchased before 1931 and are practically worn out. The remaining 10 were procured in 1934 from the Air Ministry at a nominal valuation; they are old army cooperation machines obtained so that some training with aircraft of military type might be carried out. Not a single machine is of a type fit to employ in active operations.

- Not one service air bomb is held in Canada."

This is from the book Six Years of War, the Official History of the Canadian Army, Department of National Defence. (page 6)

So, it is clear, RCAF No. 111 (F) Squadron was a part of Canada's desperate attempt to get our defences back in our own control.

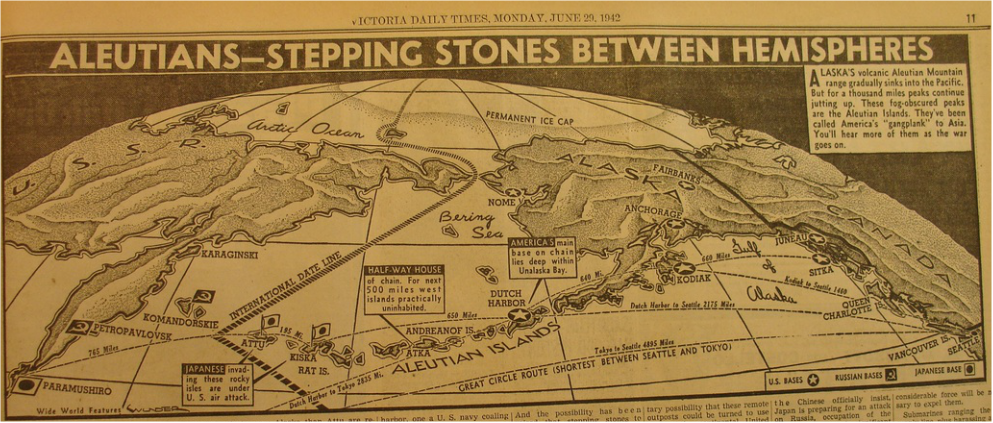

This newspaper article shows how the people of British Columbia were informed about the dangers from the West. Thanks go out to Anne Gafiuk who found and sent this image. It appeared in the Victoria Daily Times, June 29, 1942, less that three weeks after No. 111 (f) Squadron went to Alaska to take part in the defence of North America's western coast.