LIFE in 111 Squadron

Royal Canadian Air Force Championship hockey team, Kodiak Island, Alaska. Date: Fall 1942

Back row L-R: Bert Dalzell; Norm Middleton; Godfrey Holton; Bill Manzer; Ren Baker; Sunny Lundstrum. Front row, L-R: George Grindrod; "Ike" Troughton; Fred Ferris; Milt Hannigan; Merton "Ed" Burk; Tom Walsh; Ralph Nicol (only his arm is visible). All of these men were in 111 Squadron. They had an undefeated 20 game "season."

Note: According to Kathi Baker, Ren's Daughter, her Father is incorrectly identified in this picture. She said he is actually 2nd from left, back row. If so, is the guy identified as Baker actually Norm Middleton?

Identification listing on the Glenbow Archives site

This page is perpetually under construction

materials describing what service life was like on these bases during WWII will be gratefully received and added

Back row L-R: Bert Dalzell; Norm Middleton; Godfrey Holton; Bill Manzer; Ren Baker; Sunny Lundstrum. Front row, L-R: George Grindrod; "Ike" Troughton; Fred Ferris; Milt Hannigan; Merton "Ed" Burk; Tom Walsh; Ralph Nicol (only his arm is visible). All of these men were in 111 Squadron. They had an undefeated 20 game "season."

Note: According to Kathi Baker, Ren's Daughter, her Father is incorrectly identified in this picture. She said he is actually 2nd from left, back row. If so, is the guy identified as Baker actually Norm Middleton?

Identification listing on the Glenbow Archives site

This page is perpetually under construction

materials describing what service life was like on these bases during WWII will be gratefully received and added

Life in 111

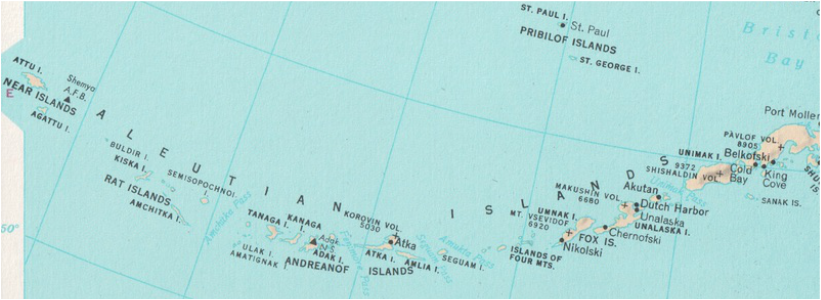

RCAF No. 111 (F) Squadron operated out of eight locations. Each setting was quite different from the others and some settings imposed very Spartan conditions. Each of the locations will be considered separately with pictures and accounts (as they become available) from the men who had the experiences.

All the western settings had one thing in common: the Pacific Ocean. Weather conditions and the challenges of learning to fly close to the surface of the water (to bomb, strafe or identify what was found there) were what exacted the greatest toll on 111 Squadron.

The settings:

RCAF Station Rockcliffe, Ottawa, Ontario (November 1, 1941 - December 13, 1941)

Patricia Bay Air Station, British Columbia (January 19, 1942 - June 3, 1942) and (August 19, 1943 - January 20, 1944)

Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska (June 8, 1942 - October 30, 1942)

detachment to: Fort Glenn Air Base, Umnak Island, Aleutians (July 16, 1942 - October 10, 1942)

Fort Greely, Kodiak Island, Alaska (October 31, 1942 - August 12, 1943)

detachment to: Chiniak Base, Kodiak Island, Alaska (November 6, 1942 - April 24, 1943)

detachment to: Fireplace Airfield, Adak Island, Aleutians (September 21,1942 - October 8,1942) and (May 4 1943 - May 14, 1943)

detachment to: Fort Richardson, Amchitka Island, Aleutians (May 15, 1943 - July 9, 1943)

All the western settings had one thing in common: the Pacific Ocean. Weather conditions and the challenges of learning to fly close to the surface of the water (to bomb, strafe or identify what was found there) were what exacted the greatest toll on 111 Squadron.

The settings:

RCAF Station Rockcliffe, Ottawa, Ontario (November 1, 1941 - December 13, 1941)

Patricia Bay Air Station, British Columbia (January 19, 1942 - June 3, 1942) and (August 19, 1943 - January 20, 1944)

Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska (June 8, 1942 - October 30, 1942)

detachment to: Fort Glenn Air Base, Umnak Island, Aleutians (July 16, 1942 - October 10, 1942)

Fort Greely, Kodiak Island, Alaska (October 31, 1942 - August 12, 1943)

detachment to: Chiniak Base, Kodiak Island, Alaska (November 6, 1942 - April 24, 1943)

detachment to: Fireplace Airfield, Adak Island, Aleutians (September 21,1942 - October 8,1942) and (May 4 1943 - May 14, 1943)

detachment to: Fort Richardson, Amchitka Island, Aleutians (May 15, 1943 - July 9, 1943)

RCAF Station Rockcliffe

(November 1, 1941 - December 13, 1941)

RCAF Station Rockcliffe, 1936

RCAF Station Rockcliffe, 1936

In early November, 1941, No. 111 (F) Squadron formed at RCAF Station Rockcliffe near Ottawa, Ontario. S/L Nesbitt took command here. He had orders to get his squadron ready to be part of the active operations in Europe. On November 8, 1941, the first pilots arrived, fresh out of Service Flying Training Schools. On November 9, the first ground crew arrived. On November 11, the first two Kittyhawks (P-40E) arrived from Curtiss-Wright, Buffalo, New York, where they had just been built.

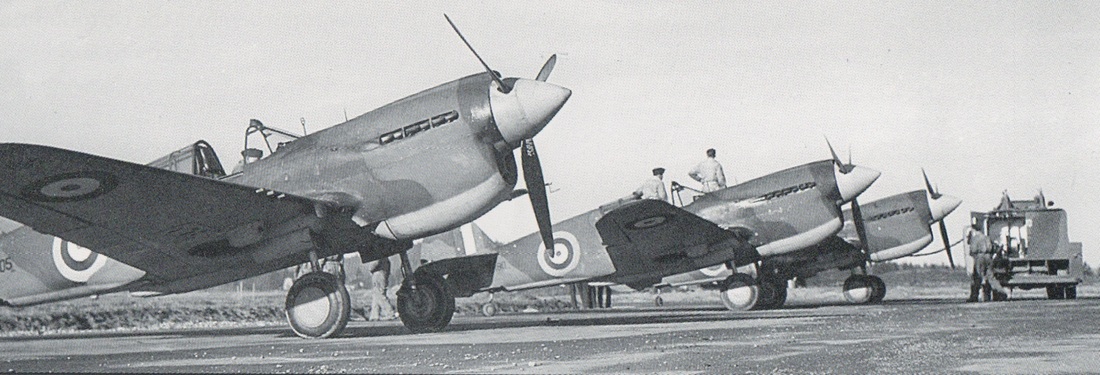

Everyone was preoccupied and busy becoming acquainted with this new aircraft type. Sergeant (Air Frame Mechanic) Lou Wise remembered that the last two weeks in November "were quite routine. New P-40E Kittyhawks were steadily arriving from the factory in Buffalo and we had to do acceptance checks on each one as it arrived. We also received a couple of Harvards and it was good to get back to working on that type again. We had to keep them all flying so that our newly minted pilots, arriving from Service Flying Training School with fresh RCAF Wings on their chests, could begin to master the single seat fighter. They had all flown Harvards at SFTS and the transition from that aircraft to the Kittyhawk was not too difficult. It was the job of the 111 (F) senior pilots with Battle of Britain experience in their log books to brief them thoroughly so they would be able to fly and gain their own experience to prepare them for the next step closer to operations in Europe.

On Sunday, December 7, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor! That would immediately change the course of action for 111 (F) Squadron. Instead of going east in early 1943, we would now go west! And we would go right away."

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had caused a major rethinking. Here is W.A.B. Douglas, in The Creation of a National Air Force (page 404) "As these great events unfolded, all forces (in Western Canada) went into a high degree of readiness. Aircraft flew continuous patrols by day. Reinforcements pushed west to fill personnel shortages. No. 111 (F) Squadron (Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks), reformed the previous month at Rockcliffe, Ont., transferred to Sea Island (Vancouver) for fighter defence."

The aircrew were not experienced enough to fly their ships all the way across the country, so the whole squadron took trains. The crated aircraft were also shipped and re-assembled at the Boeing Aircraft hanger at Sea Island Airport (now Vancouver International). According to Sergeant Lou Wise: "Once again, it was 'round the clock work assembling the aircraft ready for the pilots to arrive by rail, test fly them and then take them to Pat Bay, the RCAF Station on Vancouver Island north of Victoria, B.C. By late January, all the Kittys had gone to Pat Bay."

Everyone was preoccupied and busy becoming acquainted with this new aircraft type. Sergeant (Air Frame Mechanic) Lou Wise remembered that the last two weeks in November "were quite routine. New P-40E Kittyhawks were steadily arriving from the factory in Buffalo and we had to do acceptance checks on each one as it arrived. We also received a couple of Harvards and it was good to get back to working on that type again. We had to keep them all flying so that our newly minted pilots, arriving from Service Flying Training School with fresh RCAF Wings on their chests, could begin to master the single seat fighter. They had all flown Harvards at SFTS and the transition from that aircraft to the Kittyhawk was not too difficult. It was the job of the 111 (F) senior pilots with Battle of Britain experience in their log books to brief them thoroughly so they would be able to fly and gain their own experience to prepare them for the next step closer to operations in Europe.

On Sunday, December 7, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor! That would immediately change the course of action for 111 (F) Squadron. Instead of going east in early 1943, we would now go west! And we would go right away."

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had caused a major rethinking. Here is W.A.B. Douglas, in The Creation of a National Air Force (page 404) "As these great events unfolded, all forces (in Western Canada) went into a high degree of readiness. Aircraft flew continuous patrols by day. Reinforcements pushed west to fill personnel shortages. No. 111 (F) Squadron (Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks), reformed the previous month at Rockcliffe, Ont., transferred to Sea Island (Vancouver) for fighter defence."

The aircrew were not experienced enough to fly their ships all the way across the country, so the whole squadron took trains. The crated aircraft were also shipped and re-assembled at the Boeing Aircraft hanger at Sea Island Airport (now Vancouver International). According to Sergeant Lou Wise: "Once again, it was 'round the clock work assembling the aircraft ready for the pilots to arrive by rail, test fly them and then take them to Pat Bay, the RCAF Station on Vancouver Island north of Victoria, B.C. By late January, all the Kittys had gone to Pat Bay."

RCAF Station Patricia Bay

(January 19, 1942 - June 3, 1942) and (August 19, 1943 - January 20, 1944)

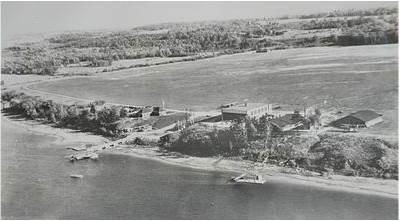

Patricia Bay is located on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. It is the site of the current Victoria International Airport. But in the early stages of the war, it was mostly grassy fields. It was the only suitably flat space in the area. See the British Columbia Aviation Museum's site that recounts Pat Bay's early days.

Patricia Bay had been the home of No. 111 (CAC) Squadron. The last day of 111 (CAC) Squadron occurred on June 30, 1940. The last operation was a Lysander flight piloted by F/O J.W. Gledhill with LAC Penny as crew. On July 1, 1940, the squadron was renamed. It became No. 111(F) Squadron. It remained as 111(F) until October 31, 1941 when it was discontinued with all personnel re-mustered and aircraft re-assigned.

A new 111 (F) Squadron was commissioned at RCAF Station Rockcliffe (Ottawa) on the same day. Service men were recruited from central Ontario and western Quebec. Then 111 (F) was re-posted to the war in the West and was sent to Patricia Bay, the same place the former 111 (F) Squadron had been stationed.

The tasks for the new 111 Squadron were for everyone involved to become more familiar with the Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk, to prepare for operational flying and then to conduct coastal patrols. There were rumours and many "sightings" of Japanese submarines so a close watch was required. In fact, during this period, the Japanese Navy had nine I-type Submarines patrolling the North American coast.

Life at Pat Bay revolved around caring for and learning to fly the new aircraft. They all lived close to the field and ate, drank and slept airplanes.

However, there were plenty of places to go on leave and between shifts. The bright lights of Victoria were only minutes away. Corporal (Armourer) Max Crandall, in his book Farm Boy Goes to War, described what it was like to be a member of 111 Squadron at Patricia Bay. Here is his recollection:

"The R.C.A.F. station at Patricia Bay was divided into two sections. On the west side ... was an all-Canadian Air Force base. On the east side... was a section occupied by RAF personnel... One-Eleven Squadron... had one hanger on this side of the airfield with these RAF boys. We ate with the RAF and all other services were provided by them. We didn't appreciate being the only Canadian unit on the east side but we had a lot of advantages that our boys across the runway didn't have. A lot of the trappings of the air force such as parades, duty watch etc. we were able to avoid - and we were close to Sidney. We could walk into Sidney anytime after work for a snack or whatever. We were only eighteen miles from Victoria, so much of our time was spent there. We still had to be in by midnight, but if we missed the last bus from Victoria, we could always stand at the corner of Quadra and Pandora and an R.C.A.F. panel wagon was sure to pick us up so as to get into camp before midnight. We were given forty-eight hour passes every ten days; so, what more could we ask for?" (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 22)

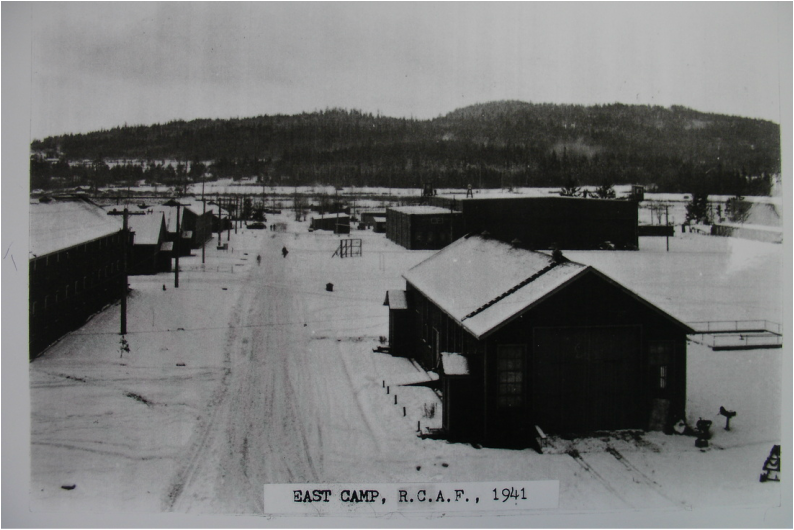

They arrived in January, 1942. Their section would have looked exactly as it had looked one year before when the picture (below) was taken.

Patricia Bay had been the home of No. 111 (CAC) Squadron. The last day of 111 (CAC) Squadron occurred on June 30, 1940. The last operation was a Lysander flight piloted by F/O J.W. Gledhill with LAC Penny as crew. On July 1, 1940, the squadron was renamed. It became No. 111(F) Squadron. It remained as 111(F) until October 31, 1941 when it was discontinued with all personnel re-mustered and aircraft re-assigned.

A new 111 (F) Squadron was commissioned at RCAF Station Rockcliffe (Ottawa) on the same day. Service men were recruited from central Ontario and western Quebec. Then 111 (F) was re-posted to the war in the West and was sent to Patricia Bay, the same place the former 111 (F) Squadron had been stationed.

The tasks for the new 111 Squadron were for everyone involved to become more familiar with the Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk, to prepare for operational flying and then to conduct coastal patrols. There were rumours and many "sightings" of Japanese submarines so a close watch was required. In fact, during this period, the Japanese Navy had nine I-type Submarines patrolling the North American coast.

Life at Pat Bay revolved around caring for and learning to fly the new aircraft. They all lived close to the field and ate, drank and slept airplanes.

However, there were plenty of places to go on leave and between shifts. The bright lights of Victoria were only minutes away. Corporal (Armourer) Max Crandall, in his book Farm Boy Goes to War, described what it was like to be a member of 111 Squadron at Patricia Bay. Here is his recollection:

"The R.C.A.F. station at Patricia Bay was divided into two sections. On the west side ... was an all-Canadian Air Force base. On the east side... was a section occupied by RAF personnel... One-Eleven Squadron... had one hanger on this side of the airfield with these RAF boys. We ate with the RAF and all other services were provided by them. We didn't appreciate being the only Canadian unit on the east side but we had a lot of advantages that our boys across the runway didn't have. A lot of the trappings of the air force such as parades, duty watch etc. we were able to avoid - and we were close to Sidney. We could walk into Sidney anytime after work for a snack or whatever. We were only eighteen miles from Victoria, so much of our time was spent there. We still had to be in by midnight, but if we missed the last bus from Victoria, we could always stand at the corner of Quadra and Pandora and an R.C.A.F. panel wagon was sure to pick us up so as to get into camp before midnight. We were given forty-eight hour passes every ten days; so, what more could we ask for?" (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 22)

They arrived in January, 1942. Their section would have looked exactly as it had looked one year before when the picture (below) was taken.

John Forbes, Air Frame Mechanic with 111 Squadron, had told his son, Don, many stories of his time in the military. Don has sent this one which he has recreated in what he remembers to be his Father's voice and cadence. This story highlights a night on the town in Victoria: "We were stationed at Pat Bay, and a small group of us got together and went on leave. We ended up going to Victoria. It was decided that we would go to this hall, and meet some gals and have a dance or two. I'm in tow with the 111 crew, and we strolled into this dance hall and had a look around. There was a couple of gals sitting near by, and we asked them if they would like to have a dance. This one gal, she looks us over and says 'we don't dance with air force,! We only dance with navy!' Well. we were a little taken aback by this so one of the guys asked her what was wrong with air force. This same gal pipes up again and says 'Air force doesn't cut it around here!' I thought to myself, here we go ! As our little group was air force, we didn't see any thing wrong with that. So, we mulled this over and decided to high tail it out of there right quick. I didn't want thing one to do with any navy type...rough bunch of characters.

So, what to do next ? Well, we found a local watering hole a ways up the street, and we got into the booze. We were all pretty "tight" when we felt it was time to move on and head off to some where else. There we are, trying not to stumble too much.

As we're making our way up the street. I get this foolish notion to cross the street. Well, I take a step off the curb, and out of nowhere, this bloody taxi cab comes roaring by (whistle) and almost ran over me. that would've been it for me, right then and there! I damn near bought it. lock,stock, and barrel ! I have no idea why I didn't just turn around, but I made it. And I'll tell you, mister man! I was well and truly sober when I got to the other side of that street.

I don't recall where in the blazes the rest of the crew I was with ended up, but I never got that soused again.

Dance or no dance, it was good to get out ."

No. 111 Squadron packed up and left Pat Bay on June 3, 1942. For the next five days they traveled, some by rail and sea, some by air, to Alaska, arriving at Anchorage on June 8, 1942.

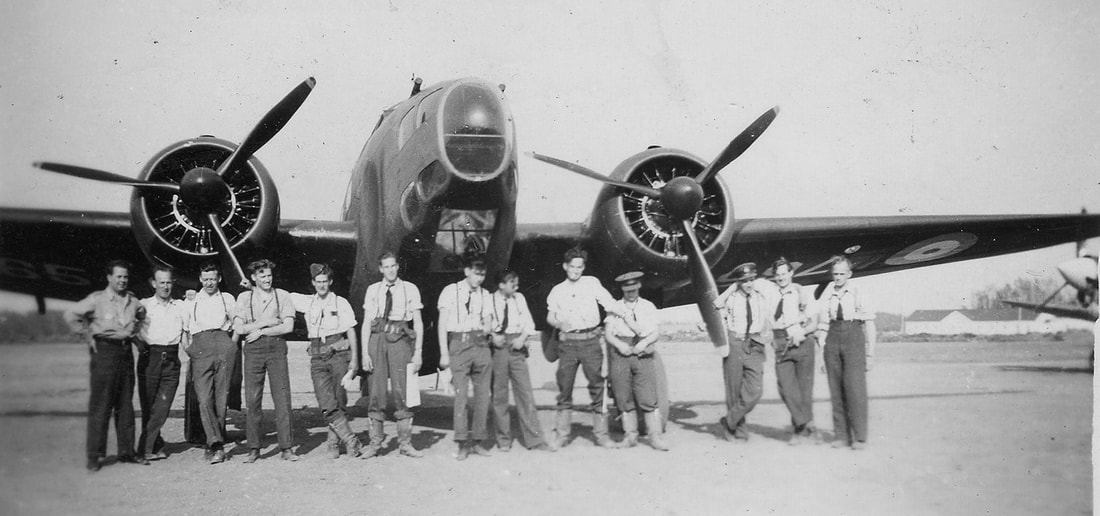

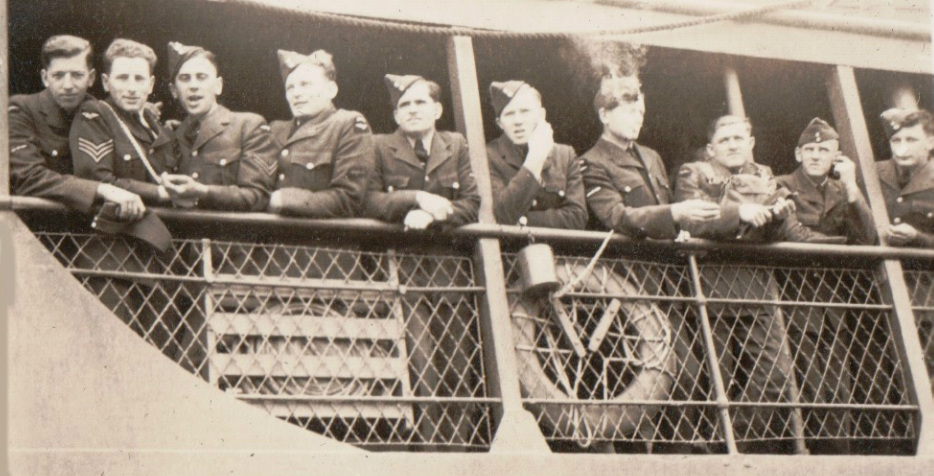

June 3, 1942, RCAF Patricia Bay, British Columbia. This group of 111 Pilots went to Anchorage with this Lockheed Hudson. I am very grateful to Allan Botting whose Father, David Edward Botting, was on the crew that flew 111 personnel to Alaska. Allan remembers his Father talking about this event. He thought that Wing Commander McGregor was in command of the mission. This picture was in his Father's Collection. I have made a stab at identifying the Pilots: L-R: Baird, Lynch, Kerwin, Schwalm, Merkley, Gooding, Ingalls, Weber, Orthman, Hicks, Gohl, Skelly, Stusiak. Please correct me if you think I have misidentified someone. Click here to Contact me.

111 Squadron served a primarily defensive role while at Elmendorf. They were to fly operations in cooperation with the USAAF 11th Pursuit Squadron. Their P-40s needed to be outfitted with long range fuel tanks and suitable bomb racks before they could go forward to the outer islands. But the parts were slow to come, delaying their getting into the action. Instead, they flew reconnaissance patrols and intercepted unidentified aircraft. Since radio communications were compromised by local atmospheric conditions, there were plenty of unidentified aircraft flying through the region. 111 Squadron was kept quite busy doing interceptions. There were numerous reports of submarine sightings (in total, during the early stages of the war, there was a fleet of nine Japanese I-boats (submarines) patrolling along the whole coastline). So, 111 was very busy in this defensive role but, all the time they were in Elmendorf, they were chafing to get into action. They derisively called this duty "flagpole flying" since they were, in their view, just going out from and returning to the base flagpole.

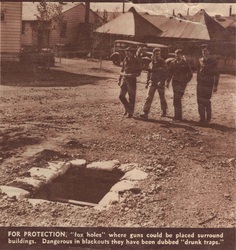

There was great concern, in early 1942, that Anchorage would be bombed. There were blackouts every night affecting the whole city.

Being a huge base, Elmendorf had its amenities.

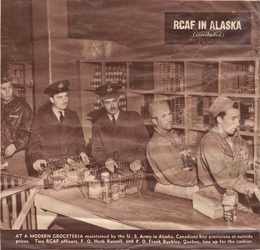

Max Crandall, armourer with 111 Squadron, described their accommodations at Elmendorf (Fort Richardson) this way: "We were bunked in long wooden barracks with one-decker beds. Here sleeping bags were issued to us as well as sheepskin jackets which every serviceman seemed to be wearing in Alaska. We ate with the Americans in their mess halls and I don't think I have ever eaten so lavishly before or since. It was the best of everything and we knew what each meal of the week would be like - but never the same meal twice in a week. The evening meal on Sunday was always roast chicken with pie and ice cream for dessert." ("Farm Boy Goes to War", page 29.)

But, even at Elmendorf, the quality of supplies was very dependent on ships getting through the tricky northern seas. We have another memory of Elmendorf during that period. John Forbes, an Air Frame Mechanic with 111 Squadron, told his son many stories of his life in the Air Force. Here is Don Forbes recollection of one of his Father's stories: "While I was in the airforce, the food was generally pretty good. When I was at Elmendorf, I recall that, for some time, the food was nothing to write home about. The only food the cooks had to feed us was macaroni with cheese and beans. As it turns out, the supply ship wasn't able to make the journey due to the water being so rough. This went on for a good four or five weeks. This one day, I had mentioned to one of my buddies that I was not becoming very fond of all this macaroni and what have you we were eating. So my buddy, he says to me, 'Johnnie, there's no food that's so bad that ketchup won't fix it.' I gave it some thought and laughed; he was right. There wasn't a whole lot one could do. We were all in the same boat, so to speak."

There was great concern, in early 1942, that Anchorage would be bombed. There were blackouts every night affecting the whole city.

Being a huge base, Elmendorf had its amenities.

Max Crandall, armourer with 111 Squadron, described their accommodations at Elmendorf (Fort Richardson) this way: "We were bunked in long wooden barracks with one-decker beds. Here sleeping bags were issued to us as well as sheepskin jackets which every serviceman seemed to be wearing in Alaska. We ate with the Americans in their mess halls and I don't think I have ever eaten so lavishly before or since. It was the best of everything and we knew what each meal of the week would be like - but never the same meal twice in a week. The evening meal on Sunday was always roast chicken with pie and ice cream for dessert." ("Farm Boy Goes to War", page 29.)

But, even at Elmendorf, the quality of supplies was very dependent on ships getting through the tricky northern seas. We have another memory of Elmendorf during that period. John Forbes, an Air Frame Mechanic with 111 Squadron, told his son many stories of his life in the Air Force. Here is Don Forbes recollection of one of his Father's stories: "While I was in the airforce, the food was generally pretty good. When I was at Elmendorf, I recall that, for some time, the food was nothing to write home about. The only food the cooks had to feed us was macaroni with cheese and beans. As it turns out, the supply ship wasn't able to make the journey due to the water being so rough. This went on for a good four or five weeks. This one day, I had mentioned to one of my buddies that I was not becoming very fond of all this macaroni and what have you we were eating. So my buddy, he says to me, 'Johnnie, there's no food that's so bad that ketchup won't fix it.' I gave it some thought and laughed; he was right. There wasn't a whole lot one could do. We were all in the same boat, so to speak."

This painting was completed in February, 2018 by Allan Botting. I am grateful to Allan for allowing me to present it here. It shows 111 Squadron's Kittyhawks flying over Alaska. He took his inspiration from a Department of National Defence photograph which was taken sometime before October 18, 1942 when all RCAF squadrons were ordered to remove the squadron ID letters. The squadron was stationed at Elmendorf Army Airbase in Anchorage at that time. By the time the squadron moved to Kodiak Island (October 31, 1942) the Squadron ID letters had been removed from all 111 Squadron aircraft. This may have been the group of planes that were detached to serve out of Umnak Island. The plane with the “D” was P-40E AK 905; RCAF # 1052. The “E” plane was AK 940, #1058. And “V” was AL 194, #1087. See picture below showing "V" being hauled from the drink.

You can see a number of Allan's aviation paintings at his site: https://sites.google.com/site/aircraftpaintings/

You can see a number of Allan's aviation paintings at his site: https://sites.google.com/site/aircraftpaintings/

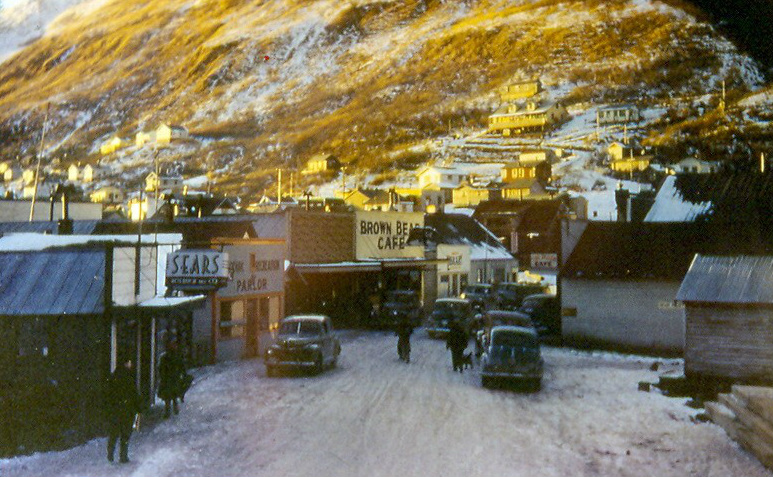

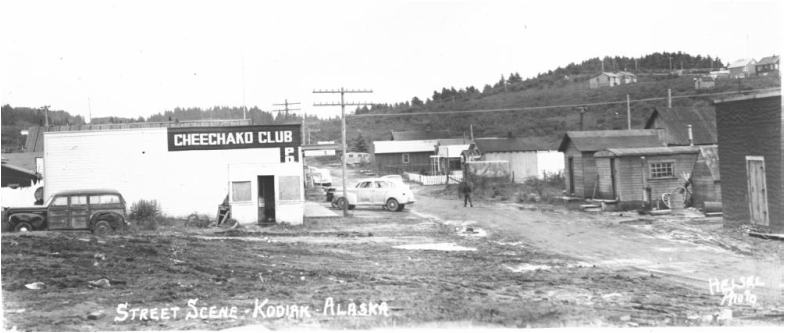

The town of Anchorage was nearby. But, according to Max Crandall who served in 111 Squadron as an armourer (in his book "Farm Boy Goes to War", page 29), "It didn't take long to get acquainted with the town of Anchorage... It had one long main street with a number of short side streets. Every second or third establishment was either a saloon or a night club such as the 'The South Seas' where alcoholic beverages were the stock in trade. The ladies of the night ran a thriving business and often queues of servicemen lined up down the street.... Lake Spenard was close by and some of us boys would manage to get out there for a swim."

T he photo of 1940's Anchorage streetscape C2005, Murray Lundberg, see this link.

T he photo of 1940's Anchorage streetscape C2005, Murray Lundberg, see this link.

The Ground Crew

The pilots seemed to get all of the press and prestige, understandably, since they took the greatest risks. But the risks would have been incalculably greater if their planes were not in tip-top shape. The guys on the ground had to be out there in any weather (and in the Aleutians the weather was as bad as it gets), prepared for any job. These pictures highlight just how complicated the task could be.

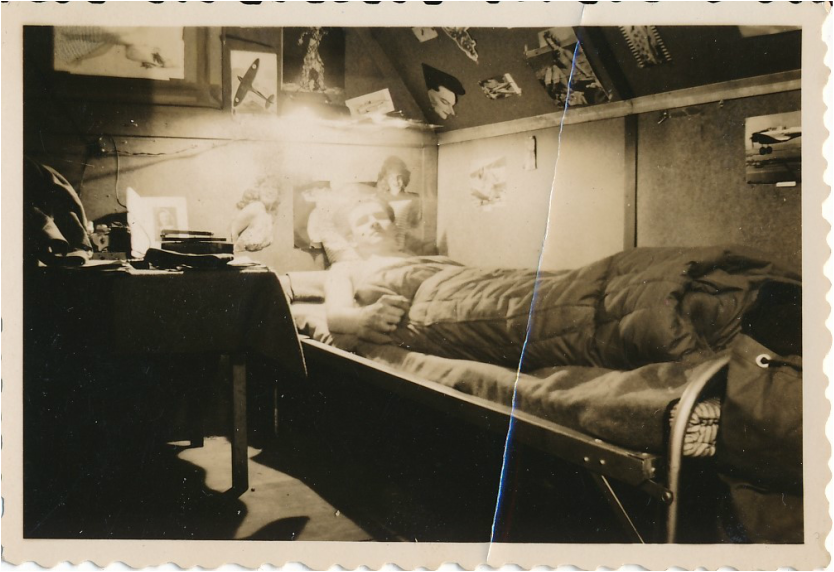

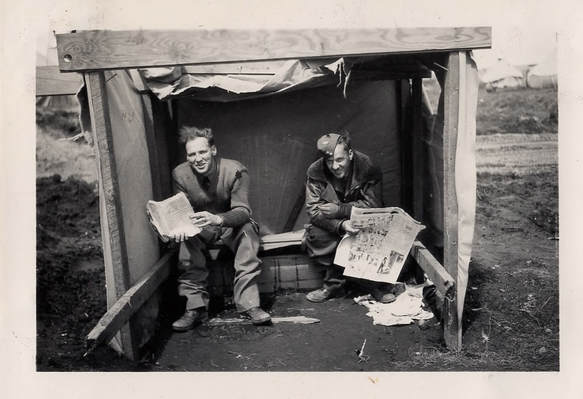

Here is crew arranging for as much comfort as can be expected at the wind-exposed base at Fort Glenn, Umnak Island. I think this is a 14 Squadron ground crew although it might 111 Squadron. I haven't been able to identify the men as yet. Help. The canvas covered "shed" could accommodate the nose only but it did protect crew from the freezing and capricious winds and driving rains.

Photo by Department of National Defence PMR 80-257, courtesy of Captain Fred Paradie

Taking advantage of a nice day, the Ground Crew are swarming (there are six men working here) over P-40E (AL 214, RCAF # 1091, Sqn ID "X"). I think this picture was taken at Fort Greely, Kodiak Island, Alaska. I have no record that "X" was damaged while in 111 Squadron's care so this must have been a general overhaul. They have removed the landing gear and are holding the a/c up with tent-like supports. Don Forbes, son of Johnnie Forbes (an Air Frame Mechanic in 111 Squadron) tells me these tent-like structures were called "trestles". Like it's from the horse's mouth, thanks, Don. Note that they are also holding it down with water-filled fuel drums. The winds could be ferocious and they were taking no chances. Note: the white box on the underside of the wing is the gun camera; note, also, the precariousness of the position of the man working on the nose. His son, Russ, thinks that this is his Father, Bill Weeks.

This is a Department of National Defence photograph but I do not have its identification number.

This is a Department of National Defence photograph but I do not have its identification number.

Here is a 111 Squadron Kittyhawk that had a hard landing, probably because the landing gear was not locked properly. That was a common problem with the early

P-40 models and with relatively inexperienced fliers. The crash had to have occurred before October 18, 1942 when all RCAF squadrons were ordered to remove squadron identification letters, presumably for security reasons. LZ were the identification letters for 111 Squadron.

Close examination of the numbers under the tailplane suggests that the final two numbers could have been 75. If so, this aircraft could have been AK 875 (RCAF #1047) which had been with 111 Squadron since its earliest days back in Rockcliffe (November, 1941).

On November 22, 1941, Pilot Officer Ingalls, after soloing in a P-40 (this P-40), in his second flight of the day, involved this a/c in a Category C accident. That might have been the mess the ground crew were working on in this picture. Since the AK 875 numbers have not yet been painted over with a rectangle of black paint, I would guess that this work was being done in the summer of 1942. They were probably at Elmendorf. It looks like there was some effort to paint out the yellow ring on the roundel, as well.

However, there was another incident involving AK 875. On July 13, 1942, the squadron flew their aircraft to Alaska. On the way, then-Pilot Officer Lynch, while approaching Naknak, had some kind of difficulty which resulted in a crash landing. His granddaughter, Karen Abel, informed me that he had recorded in his log book that, on that day (July 13, 1942), he was flying AK 875, squadron ID "T". So it is not clear which incident resulted in the damage recorded in the above photograph. It does, though, lead us into the "Mystery of BITSA".

P-40 models and with relatively inexperienced fliers. The crash had to have occurred before October 18, 1942 when all RCAF squadrons were ordered to remove squadron identification letters, presumably for security reasons. LZ were the identification letters for 111 Squadron.

Close examination of the numbers under the tailplane suggests that the final two numbers could have been 75. If so, this aircraft could have been AK 875 (RCAF #1047) which had been with 111 Squadron since its earliest days back in Rockcliffe (November, 1941).

On November 22, 1941, Pilot Officer Ingalls, after soloing in a P-40 (this P-40), in his second flight of the day, involved this a/c in a Category C accident. That might have been the mess the ground crew were working on in this picture. Since the AK 875 numbers have not yet been painted over with a rectangle of black paint, I would guess that this work was being done in the summer of 1942. They were probably at Elmendorf. It looks like there was some effort to paint out the yellow ring on the roundel, as well.

However, there was another incident involving AK 875. On July 13, 1942, the squadron flew their aircraft to Alaska. On the way, then-Pilot Officer Lynch, while approaching Naknak, had some kind of difficulty which resulted in a crash landing. His granddaughter, Karen Abel, informed me that he had recorded in his log book that, on that day (July 13, 1942), he was flying AK 875, squadron ID "T". So it is not clear which incident resulted in the damage recorded in the above photograph. It does, though, lead us into the "Mystery of BITSA".

The BITSA Stor(ies)

Here is a picture of BITSA. It looks as good as new, thanks to the efforts of Squadron 111's fitters and riggers.

But there is a bit of a mystery to the BITSA story. There is no doubt that BITSA was a 111 Squadron aircraft. But we have two post-war recollections by members of 111 Squadron of how BITSA came to be. And the stories are quite different.

I am very grateful to Don Forbes, son of Corporal Johnnie Forbes (Air Frame Mechanic with 111 Squadron), who sent his father's version of the birth of BITSA. He quoted his father: "The pilot was on his final approach. He came in too hot. He had a choice, hit a concrete abutment at the end of the runway or take to the drink. He chose the drink. A bunch of us got a truck and fished him out. We straightened her out and cleaned her up. One of the fellows got some paint and brush and painted 'BITSA' under the canopy. 'Bitsa' - built in time to save Alaska. We all laughed like hell at that."

The second recollection is substantively different. Here is Corporal (Armourer, Guns) Max Crandall's version: "As we weren't all that busy during the cold winter months (of 1943) it was arranged for a small crew to go back to the Alaskan mainland, and between Anchorage and Nak Nek (sic) they were able to pick up the pieces of that first plane that went down on our trip to Umnak about six months earlier. It was quite badly damaged but the pieces were brought back and the aircraft was rebuilt at our station in Fort Greely. It carried the identification letter "T" and when it was brought back into service, we added the letters 'BITSA' meaning now that it was a little bit of everything - not too much of the original aircraft." (Crandall, Max, A Farm Boy Goes to War, 1984, page 41)

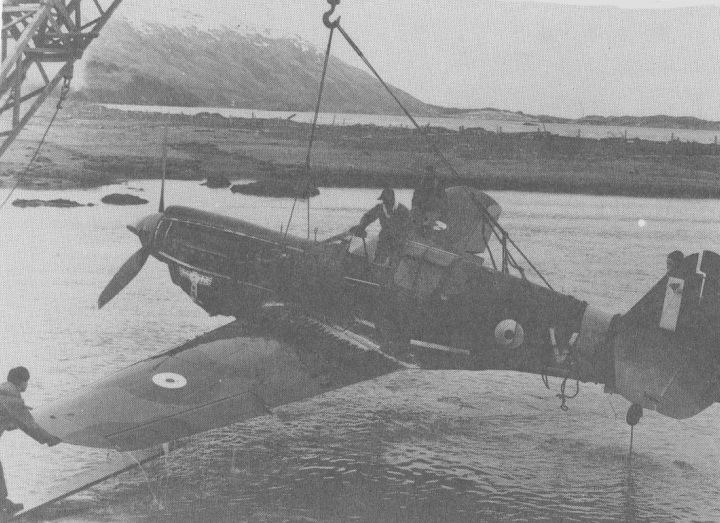

Don Forbes cannot recall if his Father ever identified the aircraft or pilot. But the only 111 aircraft that I know of that went into the drink was P-40 (AL 194, squadron Identification letter "V"). Here is the statement in the squadron Daily Diary concerning this incident: "Fort Greely, Kodiak, Alaska, April 19, 1943 At 1420 hours, W.O.2 McLeod, S.R.J., had a "C" category crash with Kittyhawk E, AL 194. He crashed off the end of the runway into the ocean. The pilot was not injured."

(P-40E, AL 194, RCAF # 1087, wore the letter "V"). See picture below.

Corporal Crandall referred to "that first plane that went down" on the way to Umnak. In fact, there were two damaged aircraft in the approaches to Naknak that day. Here is the Daily Diary account: July 7, 1942, "W/C McGregor and six pilots left Elmendorf enroute for Umnak and Cold Bay. On the way to Naknak F/Sgt Schwalm was forced to bail out due to failure of the entire electrical system. On arrival at Naknak P/O Lynch crashed on landing" Schwalm was uninjured and rescued. Lynch, too was not injured. Unfortunately, the Daily Diary (uncharacteristically) failed to identify the aircraft involved in either incident. In fact. the aircraft Schwalm was flying was P-40 E AK 989 (RCAF # 1069). The accident was rated Category "A" which would be pretty much a total write-off. I had not been able to determine which aircraft Lynch was flying. There is no record of a Squadron 111 aircraft being destroyed while landing at Naknak. However, P/O Lynch's granddaughter, Karen Abel, has contributed a vital piece of information. P/O Lynch recorded in his log book that it was AK 875 that he crash-landed in. AK 875 wore the Squadron ID letter "T".

I am assuming that the aircraft that Corporal Crandall was referring to was Lynch's AK 875. He indicated that they brought "pieces" back. And BITSA did wear the "T". According to P/O Lynch's log, he did fly AK 875 again, but not until April 24, 1943, only a few weeks after the time Corporal Crandall said the ground crew refitted the Naknak wreck.

Which account is the more accurate? Who knows? (that is not a rhetorical question)

An interesting sidebar to the AK 875 story: in 1988, the United States National Air and Space Museum added AK 875 to their collection. She can be seen hanging in the museum and tricked out in a USAAF Flying Tigers uniform, at this site. AK 875 never flew with the Flying Tigers in Burma.

But there is a bit of a mystery to the BITSA story. There is no doubt that BITSA was a 111 Squadron aircraft. But we have two post-war recollections by members of 111 Squadron of how BITSA came to be. And the stories are quite different.

I am very grateful to Don Forbes, son of Corporal Johnnie Forbes (Air Frame Mechanic with 111 Squadron), who sent his father's version of the birth of BITSA. He quoted his father: "The pilot was on his final approach. He came in too hot. He had a choice, hit a concrete abutment at the end of the runway or take to the drink. He chose the drink. A bunch of us got a truck and fished him out. We straightened her out and cleaned her up. One of the fellows got some paint and brush and painted 'BITSA' under the canopy. 'Bitsa' - built in time to save Alaska. We all laughed like hell at that."

The second recollection is substantively different. Here is Corporal (Armourer, Guns) Max Crandall's version: "As we weren't all that busy during the cold winter months (of 1943) it was arranged for a small crew to go back to the Alaskan mainland, and between Anchorage and Nak Nek (sic) they were able to pick up the pieces of that first plane that went down on our trip to Umnak about six months earlier. It was quite badly damaged but the pieces were brought back and the aircraft was rebuilt at our station in Fort Greely. It carried the identification letter "T" and when it was brought back into service, we added the letters 'BITSA' meaning now that it was a little bit of everything - not too much of the original aircraft." (Crandall, Max, A Farm Boy Goes to War, 1984, page 41)

Don Forbes cannot recall if his Father ever identified the aircraft or pilot. But the only 111 aircraft that I know of that went into the drink was P-40 (AL 194, squadron Identification letter "V"). Here is the statement in the squadron Daily Diary concerning this incident: "Fort Greely, Kodiak, Alaska, April 19, 1943 At 1420 hours, W.O.2 McLeod, S.R.J., had a "C" category crash with Kittyhawk E, AL 194. He crashed off the end of the runway into the ocean. The pilot was not injured."

(P-40E, AL 194, RCAF # 1087, wore the letter "V"). See picture below.

Corporal Crandall referred to "that first plane that went down" on the way to Umnak. In fact, there were two damaged aircraft in the approaches to Naknak that day. Here is the Daily Diary account: July 7, 1942, "W/C McGregor and six pilots left Elmendorf enroute for Umnak and Cold Bay. On the way to Naknak F/Sgt Schwalm was forced to bail out due to failure of the entire electrical system. On arrival at Naknak P/O Lynch crashed on landing" Schwalm was uninjured and rescued. Lynch, too was not injured. Unfortunately, the Daily Diary (uncharacteristically) failed to identify the aircraft involved in either incident. In fact. the aircraft Schwalm was flying was P-40 E AK 989 (RCAF # 1069). The accident was rated Category "A" which would be pretty much a total write-off. I had not been able to determine which aircraft Lynch was flying. There is no record of a Squadron 111 aircraft being destroyed while landing at Naknak. However, P/O Lynch's granddaughter, Karen Abel, has contributed a vital piece of information. P/O Lynch recorded in his log book that it was AK 875 that he crash-landed in. AK 875 wore the Squadron ID letter "T".

I am assuming that the aircraft that Corporal Crandall was referring to was Lynch's AK 875. He indicated that they brought "pieces" back. And BITSA did wear the "T". According to P/O Lynch's log, he did fly AK 875 again, but not until April 24, 1943, only a few weeks after the time Corporal Crandall said the ground crew refitted the Naknak wreck.

Which account is the more accurate? Who knows? (that is not a rhetorical question)

An interesting sidebar to the AK 875 story: in 1988, the United States National Air and Space Museum added AK 875 to their collection. She can be seen hanging in the museum and tricked out in a USAAF Flying Tigers uniform, at this site. AK 875 never flew with the Flying Tigers in Burma.

Here is BITSA again, this time wearing the squadron ID letter "S". I believe this is the same aircraft but in this photograph, its roundels and squadron ID letter are different. This type of fuselage roundel (O'Malley called it Type C1) was not used until early 1944.

In 1944, 133 Squadron was flying P-40s out of Sea Island and Patricia Bay. One of theirs was AK875. However, Walker reported that their squadron ID code was "D", not "S". Oh conundrum! Could there have been more than one BITSA?

In 1944, 133 Squadron was flying P-40s out of Sea Island and Patricia Bay. One of theirs was AK875. However, Walker reported that their squadron ID code was "D", not "S". Oh conundrum! Could there have been more than one BITSA?

W.O.2 McLeod's P-40E AL 194 (1087) being pulled out of the drink after he ran off the runway on April 19, 1943 at Fort Greely, Kodiak, Alaska. Note the Thunderbird crest on the nose. Photo: Department of National Defence #PMR 75-603

And we have another Rigger story from the inimitable AFM Sergeant, Johnny Forbes, as relayed through his son, Don. Don thinks, but he never asked John, that this event might have happened at Patricia Bay in the spring to early summer of 1942. In fact, 111 Squadron was already at Elmendorf Airbase in Anchorage, Alaska at that time. This story gives a great peek into the kinds of chores that kept Riggers busy. "One day, we had to pull the fuel tank out of the fuselage on one of the kitty's. There was three of us on the crew. We removed the canopy, then pulled the pilot's seat. The seat was adjustable, up or down, that was it ! Next, we got after the armor plate behind the seat. One of us reached back in the fuselage and disconnected the fuel lines, plugged them, and moved them out of the way. This tank held in the order of some sixty odd gallons of one hundred octane fuel. Leather straps were used to rest the tank on so it wouldn't chafe. We wrestled it out,and put it on the ground. I pushed it back and forth and rolled it around to get it back into shape. Good Lord ! what a chore that was ! After a while, we got it there ! Satisfied, we put everything back, and buttoned her up the way we found her... The pilot, as I recall, must not have switched tanks in time, and it collapsed. He did make it back OK though..."

Thanks, Don.

Thanks, Don.

The Ground Crew contained Armourers, as well as Fitters and Riggers. Here is a 111 Squadron Armourer (I think it's Max Crandall) beside some of the bombs they loaded onto the Kittyhawk.

Armourers specialized in either Bombs or Guns. Here are three 111 Squadron Armourers (Guns) at work. Cleaning the machine gun is Leading Aircraftman K. Kuykendall. Note the blast tube standing beside him (I am grateful to Dan Gory for correcting my error in thinking that this object is the gun barrel). Working on the machine gun are Leading Aircraftman Max Crandall (left) and Leading Aircraftman Ken Coutts. The aircraft is P40E AK 905 (1052) with the squadron ID letter "D". The AK 905 numbers (RAF designation) have been painted out with black paint just aft of the "D". I believed that they hadn't painted the RCAF designation (1052) on yet, but sharp-eyed Dan Gory noticed that one can see the number "1052" under the panel of black paint. I think this picture was made after the squadron left Elmendorf and was based on Kodiak Island, perhaps Spring, 1943. That coincides with the arrival of LAC Kuykendall who joined 111 Squadron at Fort Greely on May 20, 1943. Note the Thunderbird nose art. And note, too, the rolling scaffolding that allowed the Aero-Engine Mechanics to work "in comfort" on the engine.

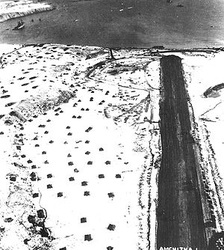

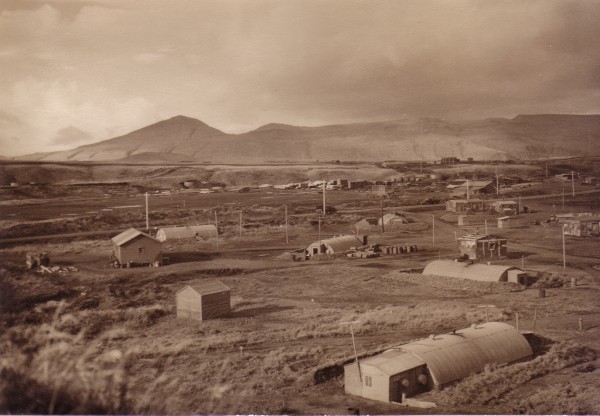

Fort Glenn Air Base, Umnak Island Photo from the Greg Krenzelok Photo Collection, courtesy of Greg Krenzelok. Thanks, Greg.

Fort Glenn Air Base, Umnak Island Photo from the Greg Krenzelok Photo Collection, courtesy of Greg Krenzelok. Thanks, Greg.

The Aleutian Islands are tiny spots in a very large ocean. Atmospheric conditions were almost always cloudy and foggy. The jutting, volcanic mountains were a constant danger to fliers struggling to see their way through mist and driving rain. The tragic crash of four 111 pilots and planes, on July 16, 1942, was into a similar mountain on neighbouring Unalaska Island. They were trying to find Umnak Island by flying as much below the clouds as they could. Suddenly, Unalaska's mountain was there. They couldn't climb fast enough and followed the leader into the side of the mountain.

The American base on Umnak Island was called Fort Glenn. They had their own airfield there. The RCAF units were installed at a satellite airfield ten miles away. The squadron Daily Diary persisted in calling it Satellite Field for the whole time 111 Squadron flew out of Umnak.

One half of the squadron was stationed on Umnak at Satellite Field while the other half was deployed to Amchitka for a month after which they rotated back and were replaced by the other half of the squadron. 111 Squadron had a presence on Umnak Island from July 13, 1942 until October 13, 1942. Flight Lieutenant (Pilot) Robert Lynch, Commander of "A" Flight of 111 Squadron while they were on Umnak, years later wrote this about their assignment: "Our training was accomplished in Anchorage mainly in learning USAF radio procedures. Our subsequent operational duties on Umnak consisted of aerodrome patrols, shared equally with the 11th Pursuit (USAAF) from dawn to dusk on a daily basis. Pilots are pilots, consequently we had no trouble blending into the routine of the 11th Pursuit's operational duties. We definitely retained our identity and our relations with the Americans could not have been better."

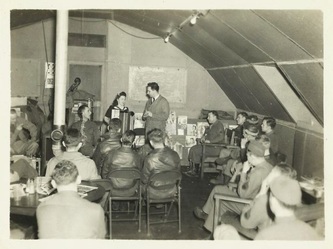

Every evening the pilots would meet for a discussion about the war situation in their sector. These meetings were led by 111's F/L Harry Thorne Mitchell, DFC who had had battle experience in Europe. He spoke about fighter tactics and did workshops with them, which the American pilots asked to attend. It was reported that all found the discussions helpful.

The real enemy was the weather. Fogs, winds, driving rains caused many hardships. A Canadian Press staff writer named Lorne Bruce was sent out to the Aleutians, particularly to Umnak Island, to get a first hand account of what conditions were like. In an article, that appeared in The Winnipeg Tribune on June 21, 1943, he gave this report: "Chief danger in the North Pacific theatre is the weather - the worst for flying in the world. Snow, rain and sleet storms come and go in minutes. Fogs roll down from the snow-covered volcanic mountains to blot out a landing strip in less than a quarter of an hour. Williwaws - strong winds that come straight down or in a verticle (sic) circle - make flying more dangerous.... PO Keeling Barrie, of Edmonton, reported seeing a fog following a plane so rapidly down a landing strip that visibility was zero in a matter of seconds after the plane was in the air. The field had been clear when the plane began its run to take off. Another time a pilot got out of his machine and walked a few yards to talk to the ground crew. When he turned around a few minutes later, the machine was upside down. The wind had picked up the plane, turned it over, and set it down almost noiselessly."

A Canadian Press staff writer named Alan Randal wrote a feature called Mess-Room Chatter that appeared in Canadian papers from time to time. He wanted Canadians to have a sense of what "our boys" were contributing to the war effort. On Friday, May 19, 1944, well after the guys of 111 Squadron had left Alaska and had gone to Europe, this appeared in the Moose Jaw Times Herald. Some time later, the Moose Jaw Times Herald Editor published the article again, with this attached note: "Editor – These ‘Mess-room Chatter’ articles were published regularly and were meant to provide a positive image of the boys overseas. Tragically, many of the boys died soon after the articles appeared. (thanks to Richard Dowson for finding this): "Canadians who have seen service in Alaska way, they’d rather fly over here... 'Somehow the feeling that the people down here are pulling for you makes a difference.” Flying Officer Clifford Hicks, Crediton, Ontario. “You know there’s more than one emergency field to land in if you can’t get home, but in Alaska if you missed the base you went into the drink.' These Alaska service men are under Wing Commander R.T.P. Davidson of Vancouver, a veteran fighter pilot. They include Flight Lieutenant Harold Gooding of Ottawa, Flight Lieutenant James Gohl of Winnipeg (Killed in Action, June 12, 1944), Flying Officers Albert Watkins of Aylesbury (and Moose Jaw) Saskatchewan, and Stanley Garside, Edmonton (Killed in Action, June 7, 1944 in France)." Notice that he re-published this fully a year and a half after 111 Squadron had left Alaska and, under new name, 440 Squadron, had been fighting in Europe. These men were still talking about the difficulties and dangers of flying in Alaska.

The American base on Umnak Island was called Fort Glenn. They had their own airfield there. The RCAF units were installed at a satellite airfield ten miles away. The squadron Daily Diary persisted in calling it Satellite Field for the whole time 111 Squadron flew out of Umnak.

One half of the squadron was stationed on Umnak at Satellite Field while the other half was deployed to Amchitka for a month after which they rotated back and were replaced by the other half of the squadron. 111 Squadron had a presence on Umnak Island from July 13, 1942 until October 13, 1942. Flight Lieutenant (Pilot) Robert Lynch, Commander of "A" Flight of 111 Squadron while they were on Umnak, years later wrote this about their assignment: "Our training was accomplished in Anchorage mainly in learning USAF radio procedures. Our subsequent operational duties on Umnak consisted of aerodrome patrols, shared equally with the 11th Pursuit (USAAF) from dawn to dusk on a daily basis. Pilots are pilots, consequently we had no trouble blending into the routine of the 11th Pursuit's operational duties. We definitely retained our identity and our relations with the Americans could not have been better."

Every evening the pilots would meet for a discussion about the war situation in their sector. These meetings were led by 111's F/L Harry Thorne Mitchell, DFC who had had battle experience in Europe. He spoke about fighter tactics and did workshops with them, which the American pilots asked to attend. It was reported that all found the discussions helpful.

The real enemy was the weather. Fogs, winds, driving rains caused many hardships. A Canadian Press staff writer named Lorne Bruce was sent out to the Aleutians, particularly to Umnak Island, to get a first hand account of what conditions were like. In an article, that appeared in The Winnipeg Tribune on June 21, 1943, he gave this report: "Chief danger in the North Pacific theatre is the weather - the worst for flying in the world. Snow, rain and sleet storms come and go in minutes. Fogs roll down from the snow-covered volcanic mountains to blot out a landing strip in less than a quarter of an hour. Williwaws - strong winds that come straight down or in a verticle (sic) circle - make flying more dangerous.... PO Keeling Barrie, of Edmonton, reported seeing a fog following a plane so rapidly down a landing strip that visibility was zero in a matter of seconds after the plane was in the air. The field had been clear when the plane began its run to take off. Another time a pilot got out of his machine and walked a few yards to talk to the ground crew. When he turned around a few minutes later, the machine was upside down. The wind had picked up the plane, turned it over, and set it down almost noiselessly."

A Canadian Press staff writer named Alan Randal wrote a feature called Mess-Room Chatter that appeared in Canadian papers from time to time. He wanted Canadians to have a sense of what "our boys" were contributing to the war effort. On Friday, May 19, 1944, well after the guys of 111 Squadron had left Alaska and had gone to Europe, this appeared in the Moose Jaw Times Herald. Some time later, the Moose Jaw Times Herald Editor published the article again, with this attached note: "Editor – These ‘Mess-room Chatter’ articles were published regularly and were meant to provide a positive image of the boys overseas. Tragically, many of the boys died soon after the articles appeared. (thanks to Richard Dowson for finding this): "Canadians who have seen service in Alaska way, they’d rather fly over here... 'Somehow the feeling that the people down here are pulling for you makes a difference.” Flying Officer Clifford Hicks, Crediton, Ontario. “You know there’s more than one emergency field to land in if you can’t get home, but in Alaska if you missed the base you went into the drink.' These Alaska service men are under Wing Commander R.T.P. Davidson of Vancouver, a veteran fighter pilot. They include Flight Lieutenant Harold Gooding of Ottawa, Flight Lieutenant James Gohl of Winnipeg (Killed in Action, June 12, 1944), Flying Officers Albert Watkins of Aylesbury (and Moose Jaw) Saskatchewan, and Stanley Garside, Edmonton (Killed in Action, June 7, 1944 in France)." Notice that he re-published this fully a year and a half after 111 Squadron had left Alaska and, under new name, 440 Squadron, had been fighting in Europe. These men were still talking about the difficulties and dangers of flying in Alaska.

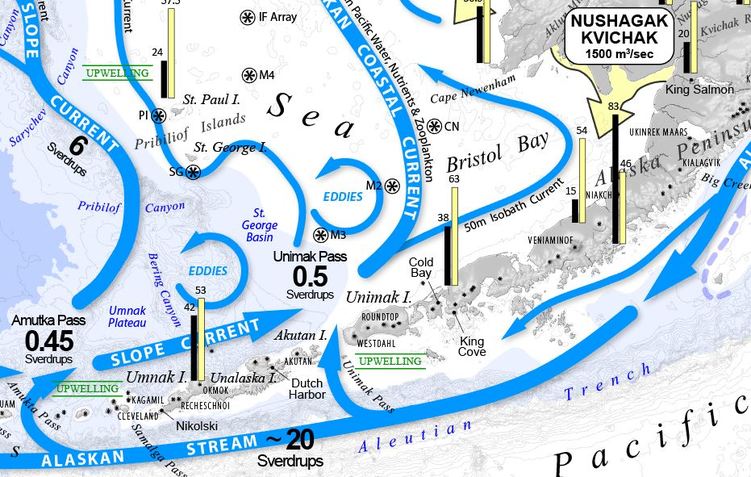

The creator of this beautiful map, Skye Cooley, can be contacted at this address. http://gis4geomorphology.com/. It demonstrates just how tricky the currents were that stirred up and mixed the frigid waters of the Bering Sea with the relatively warmer southern currents. The result: williwaws, impenetrable cloud banks, swirling fogs and, for pilots, "blindness", distorted radio transmission and unreliable instrument readings.

Another of Nature's enemies was the mosquito. They were huge, omnipresent and voracious. A USAAF Pilot, as quoted by Brian Garfield in his 1995 book The Thousand Mile War, described the pest this way: "The flight characteristics of the Alaskan mosquito have been greatly exaggerated. It is not true that they are as large as vultures. It is not true that antiaircraft outfits fresh from the States have opened fire on them, thinking they were Japanese Zeros. Their tail assembly is entirely different." Scant comfort there...

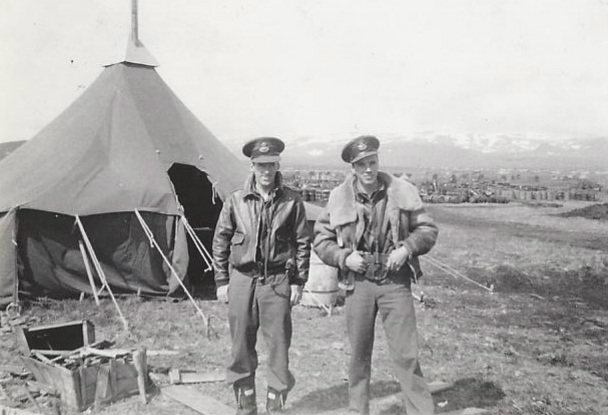

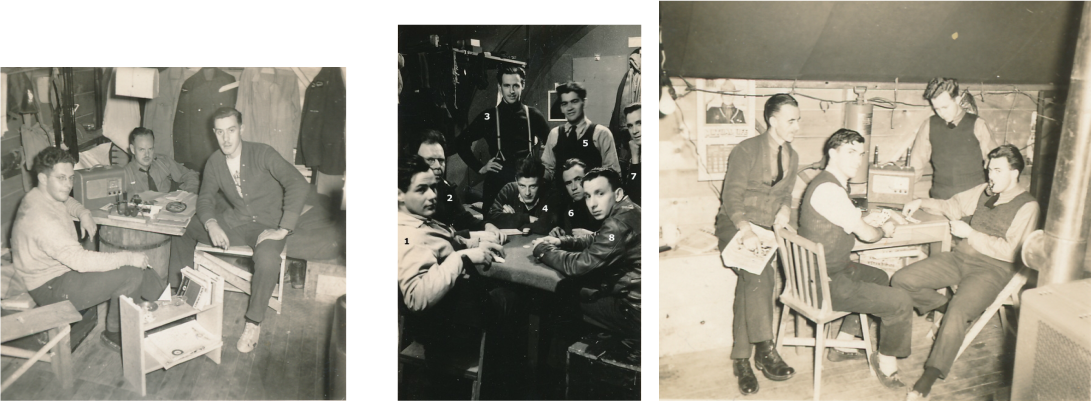

Living conditions were pretty basic. The Canadian airmen lived in square army tents. Canvas army cots and sleeping bags. The schedules of the supply ships that brought food and mail from home were controlled mostly by weather conditions. The supply lines were extremely long so nothing ever arrived fresh. Since nothing edible grows on the island, their diet was based on dehydrated and/or canned foods. It took weeks for mail from home to arrive.

According to Max Crandall, "It's doubtful anyone at home knew we were in Alaska. Our outgoing mail was all censored and our incoming mail was always addressed to us at U.S. A.P.O. #948, an Army Post office number in Seattle, Wash.; Kodiak was A.P.O. #937 and so on. In Umnak we could expect to get mail about once a month or a little better." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

To give a sense of just how limited their amenities were, at least on two occasions, according to the squadron Daily Diary, pilots flew from Satellite Airfield over to the base at Fort Glenn (10 miles) just for a shower. Gooding and Orr did it on September 13, 1942 and Gohl and Lynch did it the following day. These were in the first days of their stay there.

They had to make do without basic equipment and supplies, as well. In fact, according to the Daily Diary, they had made repeated requests for clothing that would be suitable for the windy, cold conditions and nothing had been supplied. They had to rely on the American PX for jackets and footwear. The Canadian airmen were included in the distribution of packages by the American Red Cross. The packages included pajamas, socks, books, games and playing cards and were sent to each enlisted man. The Canadians were said to be "greatly" appreciative. The Daily Diarist was moved to record the first round of packages this way: "This is the first time in the history of a Squadron that a donation of any kind has been received. We take off our hats to the good ladies of the American Red Cross." They had two such rounds of packages, one on September 7, 1942 and the other exactly one month later. On October 7, 1942, the Daily Diarist noted that they had created a new library for squadron use.

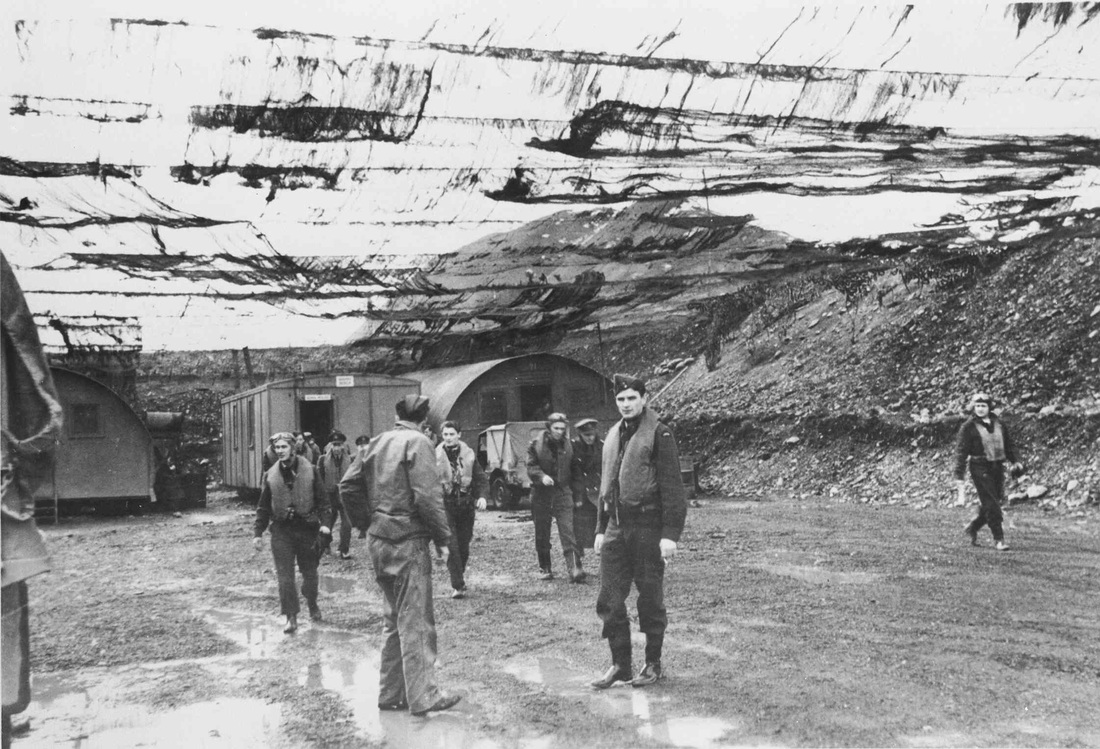

Apparently, the Canadians were inventive and made their own furniture from packing cases and their own plumbing systems with hot running water based on fuel drums and galvanized tin. The tents, of course, took a beating from the winds and storms that raged over Umnak. Max Crandall, an armourer with the squadron, remembers the role he played in making life better for them. "After one bad storm, I procured a shovel from somewhere and decided to dig myself a hole; no one else was interested so I decided to go it alone and I began digging. When the others in my tent discovered how much progress I was making, they too chipped in to help and in a few days we were down to where the weather wouldn't bother us... The idea proved to be catching, for in a few weeks all the tents occupied by Canadians, were down in the ground. Even the officers dug their own tents down. Usually officers didn't do work like that... but this was Alaska, the land of fair play, and if they wanted a hole in the ground they had to dig it, and they did - you see, it wouldn't do for officers to have second-class accommodation. Now we had all the comforts of home and some even procured used packing crates and put in walls and floors of wood. It was the best billeting west of Dutch Harbour." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

There was an official squadron Daily Diarist (from late February, 1942, it was F/O Lynch; in July, 1942, F/O Farrell assumed the role) who kept a record of the events of the day. The record was brief, sometimes enthusiastic but more typically understated and terse. Here is a sample of the daily record for several days in July, 1942 shortly after a part of the squadron began operating out of Fort Glenn. The squadron had just experienced the tragic loss of five pilots and planes on July 16, the recoveries of four of the five bodies had occurred and they were trying to get reorganized. Here are the entries:

July 23, 1942 Pilots of our squadron fly Operational Patrols from Fort Glenn. Flying one hour patrols in American ships mixed in with pilots of the 11th Pursuit (USAAF). Patrols started 04:15 grounded at 13:00 hours due to bad weather. The late S/L Kerwin and Sgt Maxmen were accorded burial with full military honors this afternoon at Fort Glenn, Alaska. Today the schedule for our pilots was completed and we are now known as (F) Flight, which consists of four American P-40's, ten pilots and our ground crew. Our temporary C.O. is P/O Lynch in charge of (F) Flight. The remainder of our squadron including five P40's still remain at Anchorage.

July 24, 1942 Our own patrols started today. Last patrol landed at 17:45 hours. Due to visibility no patrols will fly until tomorrow. W/C McGregor left this afternoon for Elmendorf Field, Anchorage. P/O Lynch still in charge here at Umnak.

July 25, 1942 Patrolling all day. Alert one hour and patrol one hour. The 111th has five sections of two planes each. Appointed section leaders are (1) P/O Lynch; (2) P/O Gohl; (3) P/O Ingalls; (4) P/O Gooding; (5) F/O Paynter.

July 26, 1942 Colonel D.F. Zanuck, famous Motion Picture Executive arrived today with intention of shooting scenes for a picture. Pilots of our squadron and pilots of 11th Pursuit (USAAF) took part in personnel scenes and scrambles. Tomorrow scenes of 111th will be taken.

July 27, 1942 Patrols started early today as usual but conditions changed quickly. Within five minutes from a good ceiling of 900 feet, the runways were completely closed in. Due to good work of patrols and the pilots, no patrols were caught off guard. Movie scenes that were taken today were of the Alaska Unit. Ten of our chaps were included.

July 28, 1942 Heavy ground fog hindered flying. In the afternoon had a ceiling of 6 to 700 feet. A new runway has been completed parallel to steel mesh runway. Pilots made circuits to get the feel of the new runway. Dirt runway greatly favored, as the other is hard on aircraft and makes landing difficult. Living conditions are improving. Five men to a tent with sleeping bags and four blankets per man. Homemade furniture being made up by everyone in spare moments. Cooperation has been 100%."

There was little for them to do there when they were not on shift. They organized a volleyball league and played every evening they could, frequently three games per evening.

Max Crandall had something to say about the use of alcohol. "There was no liquor on the Island of Umnak so there was a tendency for airmen to consume just about anything that had alcohol in it, such as lemon extract, shoe polish and another popular one they called 'torpedo juice'. It was pure alcohol and I don't really know why it was available on the island; maybe the P.B.Y.'s used torpedoes. So it was decided that one time when a DC-3 was coming down from Fort Richardson, a sizable quantity of liquor was put on board. You know, most of our crews weren't much good for anything for several days - they weren't too bad as long as the liquor held out but the return to normal was a bad time. Tempers could get real short."

(Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

According to the Daily Diary, on the evening of August 12, 1942, the pilots of USAAF Squadron 11 (Kittyhawks) and Squadron 54 (P-38 Lockheed Lightnings) invited all pilots of "The Canadian Thunderbirds" to a "Pursuit Festival" which the Daily Diary described as "an outpost party with no facilities except tin cans as cups. The drinks were known as Torpedo Cocktails - torpedo alcohol, grapefruit juice, peach juice and water." The diary was mute as to their condition the following morning except to say (perhaps archly) that the visibility was obscured by low ceiling and that patrols started at 09:15.

Living conditions were pretty basic. The Canadian airmen lived in square army tents. Canvas army cots and sleeping bags. The schedules of the supply ships that brought food and mail from home were controlled mostly by weather conditions. The supply lines were extremely long so nothing ever arrived fresh. Since nothing edible grows on the island, their diet was based on dehydrated and/or canned foods. It took weeks for mail from home to arrive.

According to Max Crandall, "It's doubtful anyone at home knew we were in Alaska. Our outgoing mail was all censored and our incoming mail was always addressed to us at U.S. A.P.O. #948, an Army Post office number in Seattle, Wash.; Kodiak was A.P.O. #937 and so on. In Umnak we could expect to get mail about once a month or a little better." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

To give a sense of just how limited their amenities were, at least on two occasions, according to the squadron Daily Diary, pilots flew from Satellite Airfield over to the base at Fort Glenn (10 miles) just for a shower. Gooding and Orr did it on September 13, 1942 and Gohl and Lynch did it the following day. These were in the first days of their stay there.

They had to make do without basic equipment and supplies, as well. In fact, according to the Daily Diary, they had made repeated requests for clothing that would be suitable for the windy, cold conditions and nothing had been supplied. They had to rely on the American PX for jackets and footwear. The Canadian airmen were included in the distribution of packages by the American Red Cross. The packages included pajamas, socks, books, games and playing cards and were sent to each enlisted man. The Canadians were said to be "greatly" appreciative. The Daily Diarist was moved to record the first round of packages this way: "This is the first time in the history of a Squadron that a donation of any kind has been received. We take off our hats to the good ladies of the American Red Cross." They had two such rounds of packages, one on September 7, 1942 and the other exactly one month later. On October 7, 1942, the Daily Diarist noted that they had created a new library for squadron use.

Apparently, the Canadians were inventive and made their own furniture from packing cases and their own plumbing systems with hot running water based on fuel drums and galvanized tin. The tents, of course, took a beating from the winds and storms that raged over Umnak. Max Crandall, an armourer with the squadron, remembers the role he played in making life better for them. "After one bad storm, I procured a shovel from somewhere and decided to dig myself a hole; no one else was interested so I decided to go it alone and I began digging. When the others in my tent discovered how much progress I was making, they too chipped in to help and in a few days we were down to where the weather wouldn't bother us... The idea proved to be catching, for in a few weeks all the tents occupied by Canadians, were down in the ground. Even the officers dug their own tents down. Usually officers didn't do work like that... but this was Alaska, the land of fair play, and if they wanted a hole in the ground they had to dig it, and they did - you see, it wouldn't do for officers to have second-class accommodation. Now we had all the comforts of home and some even procured used packing crates and put in walls and floors of wood. It was the best billeting west of Dutch Harbour." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

There was an official squadron Daily Diarist (from late February, 1942, it was F/O Lynch; in July, 1942, F/O Farrell assumed the role) who kept a record of the events of the day. The record was brief, sometimes enthusiastic but more typically understated and terse. Here is a sample of the daily record for several days in July, 1942 shortly after a part of the squadron began operating out of Fort Glenn. The squadron had just experienced the tragic loss of five pilots and planes on July 16, the recoveries of four of the five bodies had occurred and they were trying to get reorganized. Here are the entries:

July 23, 1942 Pilots of our squadron fly Operational Patrols from Fort Glenn. Flying one hour patrols in American ships mixed in with pilots of the 11th Pursuit (USAAF). Patrols started 04:15 grounded at 13:00 hours due to bad weather. The late S/L Kerwin and Sgt Maxmen were accorded burial with full military honors this afternoon at Fort Glenn, Alaska. Today the schedule for our pilots was completed and we are now known as (F) Flight, which consists of four American P-40's, ten pilots and our ground crew. Our temporary C.O. is P/O Lynch in charge of (F) Flight. The remainder of our squadron including five P40's still remain at Anchorage.

July 24, 1942 Our own patrols started today. Last patrol landed at 17:45 hours. Due to visibility no patrols will fly until tomorrow. W/C McGregor left this afternoon for Elmendorf Field, Anchorage. P/O Lynch still in charge here at Umnak.

July 25, 1942 Patrolling all day. Alert one hour and patrol one hour. The 111th has five sections of two planes each. Appointed section leaders are (1) P/O Lynch; (2) P/O Gohl; (3) P/O Ingalls; (4) P/O Gooding; (5) F/O Paynter.

July 26, 1942 Colonel D.F. Zanuck, famous Motion Picture Executive arrived today with intention of shooting scenes for a picture. Pilots of our squadron and pilots of 11th Pursuit (USAAF) took part in personnel scenes and scrambles. Tomorrow scenes of 111th will be taken.

July 27, 1942 Patrols started early today as usual but conditions changed quickly. Within five minutes from a good ceiling of 900 feet, the runways were completely closed in. Due to good work of patrols and the pilots, no patrols were caught off guard. Movie scenes that were taken today were of the Alaska Unit. Ten of our chaps were included.

July 28, 1942 Heavy ground fog hindered flying. In the afternoon had a ceiling of 6 to 700 feet. A new runway has been completed parallel to steel mesh runway. Pilots made circuits to get the feel of the new runway. Dirt runway greatly favored, as the other is hard on aircraft and makes landing difficult. Living conditions are improving. Five men to a tent with sleeping bags and four blankets per man. Homemade furniture being made up by everyone in spare moments. Cooperation has been 100%."

There was little for them to do there when they were not on shift. They organized a volleyball league and played every evening they could, frequently three games per evening.

Max Crandall had something to say about the use of alcohol. "There was no liquor on the Island of Umnak so there was a tendency for airmen to consume just about anything that had alcohol in it, such as lemon extract, shoe polish and another popular one they called 'torpedo juice'. It was pure alcohol and I don't really know why it was available on the island; maybe the P.B.Y.'s used torpedoes. So it was decided that one time when a DC-3 was coming down from Fort Richardson, a sizable quantity of liquor was put on board. You know, most of our crews weren't much good for anything for several days - they weren't too bad as long as the liquor held out but the return to normal was a bad time. Tempers could get real short."

(Farm Boy Goes to War, page 35)

According to the Daily Diary, on the evening of August 12, 1942, the pilots of USAAF Squadron 11 (Kittyhawks) and Squadron 54 (P-38 Lockheed Lightnings) invited all pilots of "The Canadian Thunderbirds" to a "Pursuit Festival" which the Daily Diary described as "an outpost party with no facilities except tin cans as cups. The drinks were known as Torpedo Cocktails - torpedo alcohol, grapefruit juice, peach juice and water." The diary was mute as to their condition the following morning except to say (perhaps archly) that the visibility was obscured by low ceiling and that patrols started at 09:15.

This photo from the G.L. Krenzelok Collection and posted at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gregkrenzelok Mr. Krenzelok wrote:

August 5, 2013 – I received this email from Stephen Briscuso:

Hello Greg

Thought you may like this photo of Radio Station WXLA that I believe my father, Sgt. Salvatore (Sam) Briscuso took when he was stationed on Umnak Island in 1943. My dad passed away in 1989.

Thanks.....Stephen Briscuso

This photo from the G.L. Krenzelok Collection and posted at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gregkrenzelok Mr. Krenzelok wrote:

August 5, 2013 – I received this email from Stephen Briscuso:

Hello Greg

Thought you may like this photo of Radio Station WXLA that I believe my father, Sgt. Salvatore (Sam) Briscuso took when he was stationed on Umnak Island in 1943. My dad passed away in 1989.

Thanks.....Stephen Briscuso

They did have radio. An Umnak Island radio station brought music and news. One of the broadcasters of the day was Jay Street. In an e-mail to rootsweb at ancestry.com, dated February 20, 2012, Jay Street wrote: "Viewed your pictures today and remember many of those sites, especially the radio station and the manager there was Ed Moser, sitting in front of the console. I worked with Ed and was a disc jockey/ announcer during 43 & 44 and part of 45. We used to put the island to bed with a nightcap signoff featuring the King Sisters singing 'Nighty Night Till Tomorrow' and Vonnie King, would get real close to the microphone and say those words. The radio stations call letters were WXLA on Umnak." It's as if we were there, Jay. Thanks for the memory.

Ground crew, at the Satellite Base on Umnak Island, had these nose sheds that gave a little protection from squalls and wind. There is a mix of 111 Squadron and 14 squadron P-40's here. The one in the foreground is 111's P-40 Mk I, AK905 (RCAF # 1052). Note the underlkined squadron ID letter. I think 111 Squadron was the only one among the Alaska squadrons that used the underline. Photo Department of National Defence PL 13210, courtesy of Captain Fred Paradie.

Satellite Field Airbase, Umnak Island. Mt Tulik is barely discernible in the background of the upper photo. It is not hard to imagine that the towering volcanic mountains along the Aleutian Chain were as hazardous to aircraft as they were beautiful. The bottom photo shows a detachment (either from 14 Squadron or 111 Squadron) arriving to begin their rotation on Umnak. The pilots flew their P-40s in and the spare pilots, ground crew and support staff came in on the C-47 which was, no doubt, piloted by USAAF's Captain Fillmore. (Both photos from Department of National Defence: The top one is PMR 79-622, the bottom photo is PMR 79-536; both courtesy of Captain Fred Paradie)

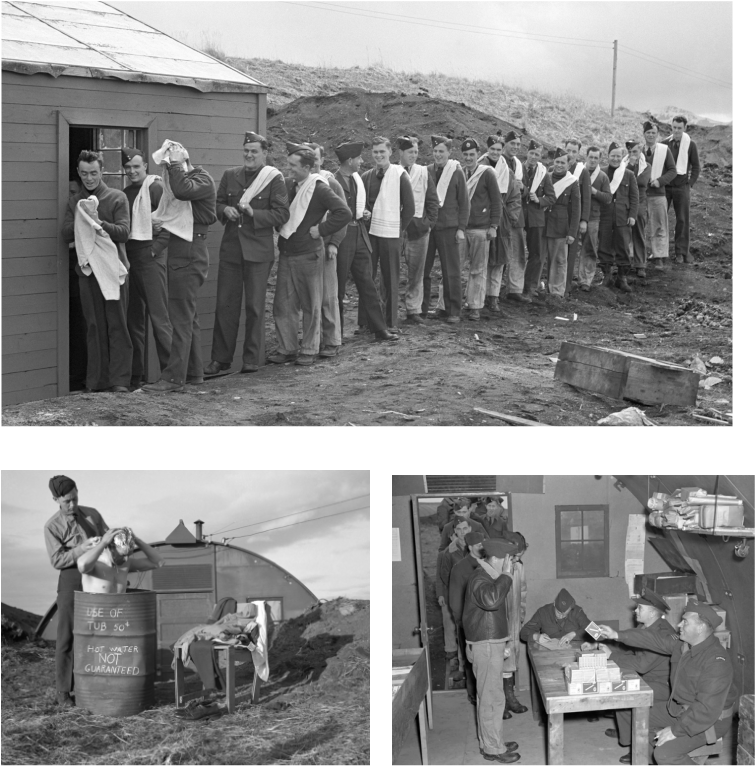

Conditions on the Aleutian Islands were very basic. Community shower facilities for the Enlisted Men were limited and in demand. The bathing pictures look posed, the top one probably on the occasion of the issuing of new, clean towels. The barrel picture looks jokey but they probably did bathe in barrels. Certainly, empty fuel barrels would have been readily available for such use. I don't know which squadron these men belonged to but all squadrons had the same conditions. The bottom right picture shows a typical line-up. Here for pay parade and the issuance of cigarette allotment. (Photo: All by the Department of National Defence, PL 13083, PL13082 and PL 13154 courtesy of Captain Fred Paradie.)

Fireplace Airfield, Adak Island, Aleutians

September 21,1942 - October 8,1942 and May 4 1943 - May 14, 1943

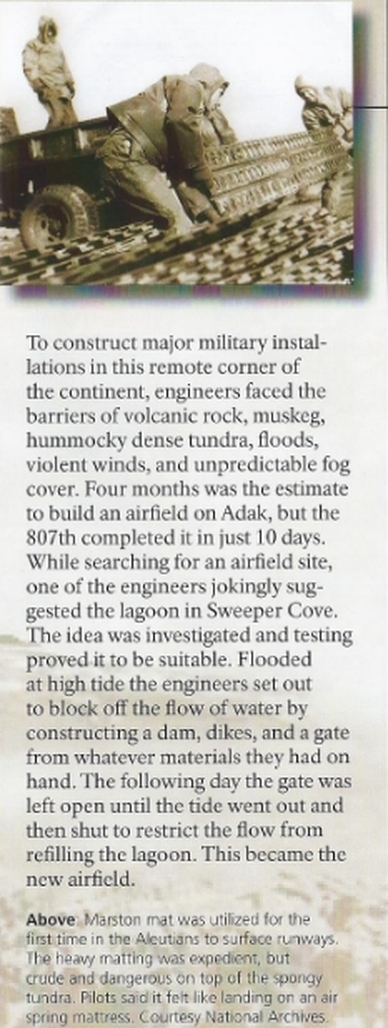

Photo and copy from War in the Aleutians 1942 - 1945, a 2009 Calendar featuring the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area. It was produced by the U.S. National Park Service. It appears here courtesy of Anne and Bo Jensen.

Photo and copy from War in the Aleutians 1942 - 1945, a 2009 Calendar featuring the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area. It was produced by the U.S. National Park Service. It appears here courtesy of Anne and Bo Jensen.

The distance between Umnak Island and Kiska Island (where the Japanese forces were dug in) was about 650 miles, too far for a loaded P-40 to attack and make it safely home. So an island in between them was chosen to be the site of an advanced base. Adak Island filled the bill. Flat land could be created (see insert) for runways and it was only 250 miles from Kiska, a manageable distance for the P-40s with belly tanks.

From late in 1942 until well into the Winter of 1943, the USAAF 11th Pursuit Squadron flew sorties from Umnak Island through Adak Island (where they refueled) to Kiska. Two RCAF Squadrons, 111 and 14, took two-week rotations living and flying from Adak. 111 Squadron took the first shift on Adak beginning on September 21, 1942 and lasting until October 8. One half of 111 Squadron remained on Umnak Island, the other on Adak. They returned to Adak again between May 4 and May 14, 1943. Their principal role was to patrol and provide security for the installation.

The weather did not improve, however. The guaranteed weather report for any day that September anticipated rain and wind. To get an idea of what it must have been like to fly out of Fireplace and return to it, look at this film clip. (Alaska Film Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, John Huston narrating) I'm not sure which island airstrip is shown in the clip but, in the Aleutians, weather conditions could be counted on to be trying, no matter where you were. The clip shows Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and Bell P-39 Airacobras, not Kittyhawks, but you do see the difficulties they faced.

Yet, between them, the two Canadian squadrons managed to fly 60 sorties out of Adak. And they did it without mishap.

Their mission, at first, was primarily defensive but they chafed at having to play a defensive role. They wanted their turn at the enemy.

There was great elation when it was announced that members of both Canadian squadrons were to be included in a major raid against the enemy on Kiska.

In some respects, the raid on the Japanese-held Kiska Island represented the dramatic high point for 111 (f) Squadron.

Here is how the events unfolded as recorded in the squadron's Daily Diary:

(Note: throughout the record, there seems to have been little unanimity as to whether the field on Adak Island was called Fireplace or Fireside, somewhere I saw it referred to as Flashlight. I will use Fireplace.

September 16, 1942 Umnak Island

Squadron Leader Boomer flew over in the afternoon from the main field (Fort Glenn, Umnak Island) and from him we learned of an intended fighter sweep from Fireside (sic) to Kiska in which some of our pilots will take part.

September 18, 1942 Umnak Island

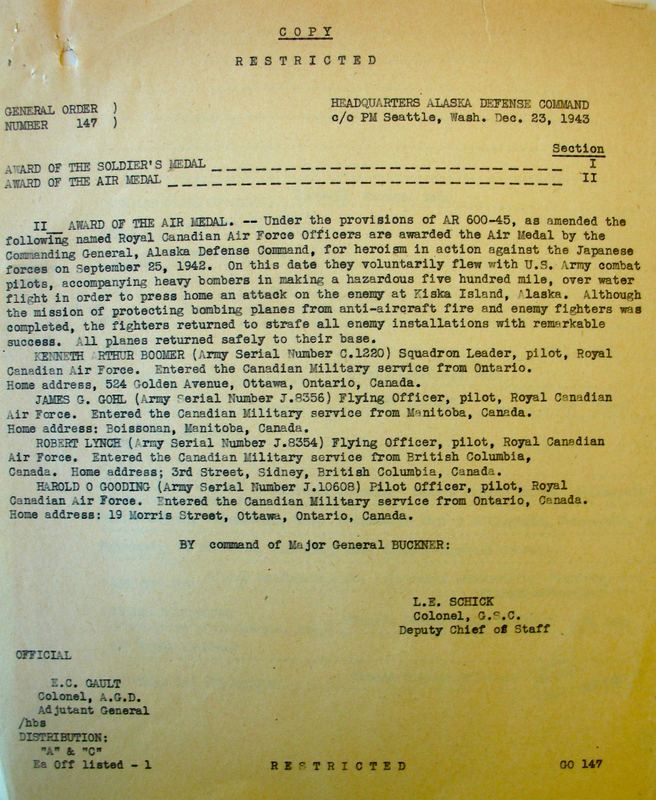

Three pilots were picked to accompany Squadron Leader Boomer on the strafing party to Kiska. They were Flying Officers Lynch and Gohl and Pilot Officer Gooding. The 11th Pursuit Squadron has to provide eight pilots in the charge of Major Chennault and the 18th (F) squadron to provide eight pilots under Major J.L. Goyle.

September 19, 1942 Umnak Island

The Kiska mission was called off on account of weather conditions.

September 20, 1942 Umnak Island

Pilots were due to take off at 13:30 hours for the Kiska mission but a terrific wind and rain storm came up and it was called off again.

September 21, 1942 Umnak Island

At 12:30 hours today, Squadron Leader Boomer, Flying Officers Gohl and Lynch and Pilot Officer Gooding took off with the American pilots for Fireplace enroute to Kiska. Prior to taking off the ship piloted by the Squadron Leader blew a tail tire and he had to change ships. Fast work by the ground crew did not delay the proceedings. Bon voyage as this is the first time the squadron has had a chance for real action against the Japs.

Our part in the raid will consist of strafing the naval emplacements primarily and a general ground strafe.

September 23, 1942 Umnak Island

No word as yet on the Kiska Mission. Everyone anxious to ascertain the results.

An addendum to the Diary called Appendix Three was the Squadron Leader's summary of the raid:

"September 25, 1942

Summary of Operational Mission on Kiska Squadron Leader K.A. Boomer, Flying Officers R. Lynch, J. G. Gohl, and Pilot Officer H.O. Gooding departed from Fort Glenn at 1330 hours, 22-9-42 to refuel at Fireplace, then to strafe Kiska. The mission consisted of 9 B-24's, 12 P-39's and 20 P-40's. The aircraft landed at Fireplace at 1600 hours, 22-9-42, refueling by all crews was carried out, and the following morning at 0900 hours the aircraft took off to complete the mission. Heavy rainstorms and poor visibility was encountered for approximately one hour's flying, and the aircraft were forced to turn back, weather necessitating the aircraft ascending to 17,000 feet on the return trip. One American aircraft was lost, supposedly due to weather, and the planes landed at 11:45 hours. Continued bad weather prevented the operation from being carried out until the morning of the 25th. At 0800 hours, 25-9-42 the aircraft again took off, and the weather was good throughout the trip. We arrived at Kiska harbour at approximately 10:00 hours. The Canadian Flight crossed Little Kiska Island, experiencing little fire from that point. Crossing the north head of the Harbour they heavily attacked naval gun emplacements and also several 50 calibre guns, continuing they attacked the main camp area and Squadron Leader Boomer with Pilot Officer Gooding also attacked enemy Radar Stations. Turning right the formation re-crossed the north head again attacking gun emplacements. Inside the Harbour area one enemy zero fighter float plane was encountered and destroyed by Squadron Leader Boomer. After circling the harbour, an enemy submarine was discovered also being attacked by American pilots. Canadians joined in this and made several attacks each. The formation then joined the B-24's, five miles east of Segula Island and returned to the base at Fireside (sic), landing at 11:50 hours.