Sacrifices

Flying was highly romanticized and young men yearned for the freedom of the air and to "touch the face of God."

And the RCAF knew how to capture that imagination.

Here is a sample of the type of posters that could be found in every public

building in the Country in the early 1940s.

War was "Adventure in the skies!" C'mon for the adventure!

Nevertheless, RCAF pilots were expected to fight - not with their fists, of course, but with their machines. They had to learn skills and disciplines: formation flying, dive bombing, flying under the cloud cover, navigation, instrument flying, shooting to hit from a moving platform, dogfighting. Such skills were not learned easily; mistakes could be costly.

Military aviation had a nasty and dangerous side to it.

Here is a sample of the type of posters that could be found in every public

building in the Country in the early 1940s.

War was "Adventure in the skies!" C'mon for the adventure!

Nevertheless, RCAF pilots were expected to fight - not with their fists, of course, but with their machines. They had to learn skills and disciplines: formation flying, dive bombing, flying under the cloud cover, navigation, instrument flying, shooting to hit from a moving platform, dogfighting. Such skills were not learned easily; mistakes could be costly.

Military aviation had a nasty and dangerous side to it.

Many pilots did not survive the war.

Some did not survive their stint with 111 Squadron.

April 19, 1942, Sergeant Pilot Douglas Leslie Stapleton crashed at sea and was lost in a training accident. His body was never recovered. The Pacific Ocean is his burial ground.

May 12, 1942, Sergeant Pilot Richard Roland Thomas Christy crashed

and drowned in a training accident.

July 7, 1942, Pilot Officer/ Pilot Donald John Sterling died in a routine training accident. The aircraft he was flying was a Cessna Crane (#8671), a wooden multi-engine primary trainer (The one shown here is currently on display in the Canadian Heritage Warplane Museum). Two other airmen were with him and were also killed. They were Sergeant (Pilot) Harold Milton Miners (age 20) from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan and Aircraftman 1 Edmund James Delaney, 31, from Toronto (a member of the Ground Crew, along for the ride, I think). They were part of RCAF Squadron No. 147 (Bomber Reconnaisance) and flying out of their home base of Sea Island (Vancouver). Sergeant Miners' Great Nephew has his Great Uncle's Flight Log. It shows that P/O Sterling and Sgt/Pilot Miners, in recent days, both had had a turn at being First Pilot in training flights in Cranes. Indeed, F/O Sterling was First Pilot on the fatal flight. Both were young men of 20, new pilots, transitioning into multi-engine aircraft.

Sgt/Pilot Miners, at #2 SFTS, Uplands, Ontario, had trained as a single engine pilot, probably slated to be a fighter pilot. When he arrived at Western Air Command, his first assignment was to 14 Squadron, a P-40 fighter squadron. He was there only a couple of weeks. Then he was reassigned to 147 BR (bomber) Squadron on June 15, 1942. His flight log showed that, after arriving at 147 Squadron, he had had some orientation flights in multi-engine aircraft and that he had flown the Crane as First Pilot. But his training in multi-engine craft was not complete. In the fatal flight, these young pilots were flying routine training circuits, familiarizing themselves with the different handling characteristics of multi-engine aircraft. Once fully operational, they would have been flying Bristol Bolingbrokes on anti-submarine patrols in the protection of Vancouver and Victoria. Later on, their squadron moved on to Tofino, Vancouver Island but without them. They crashed and burned three miles east of Sea Island, on Lulu Island. The cause is not known.

Sgt/Pilot Miners, at #2 SFTS, Uplands, Ontario, had trained as a single engine pilot, probably slated to be a fighter pilot. When he arrived at Western Air Command, his first assignment was to 14 Squadron, a P-40 fighter squadron. He was there only a couple of weeks. Then he was reassigned to 147 BR (bomber) Squadron on June 15, 1942. His flight log showed that, after arriving at 147 Squadron, he had had some orientation flights in multi-engine aircraft and that he had flown the Crane as First Pilot. But his training in multi-engine craft was not complete. In the fatal flight, these young pilots were flying routine training circuits, familiarizing themselves with the different handling characteristics of multi-engine aircraft. Once fully operational, they would have been flying Bristol Bolingbrokes on anti-submarine patrols in the protection of Vancouver and Victoria. Later on, their squadron moved on to Tofino, Vancouver Island but without them. They crashed and burned three miles east of Sea Island, on Lulu Island. The cause is not known.

I am grateful to Sergeant (Pilot) Miners' Great Nephew, Hi Brooks, who has been trying to learn as much as he can about his Great Uncle's wartime experience and his death. He enclosed this photograph of the newly-minted pilot, Sergeant Harold Milton Miners, age 20, standing in front of his parents' home in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, on leave, while he transited from "Y" Depot, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia (Eastern Air Command) to Vancouver (Western Air Command). He had completed pilot's basic training in Ottawa and, I think, was sent to "Y" Depot to prepare to go overseas. But in mid-1942, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the RCAF, which had been preparing primarily to have pilots and airmen ready to go to Europe, suddenly redirected a lot of trained people to the west coast. Sergeant Miners was one of them. So was P/O Sterling. It was not unusual, under those circumstances, to retrain fighter pilots to fly bombers, because they were using light bombers for anti-submarine patrols over the ocean. At the time he joined 147 Squadron, it was just forming. It would not become operational until November 7, 1942.

He was the son of C.M. and Emma Miners. Sergeant Pilot Miners was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

I know nothing about AC1 Edmund James Delaney, 31, who died with him. If you do and would like to share with others, I would be pleased to post it here.

He was the son of C.M. and Emma Miners. Sergeant Pilot Miners was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

I know nothing about AC1 Edmund James Delaney, 31, who died with him. If you do and would like to share with others, I would be pleased to post it here.

The Disastrous Relocation Flight

July 16, 1942, Squadron Leader (Pilot) John William Kerwin crashed into fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska.

July 16, 1942, Flight Sergeant (Pilot) Frank "Pop" Lennon crashed into fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska

July 16, 1942, Sergeant (Pilot) Stanley Ray Maxmen crashed into a fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska.

July 16, 1942, Pilot Officer (Pilot) Dean Edward "Whitey" Whiteside crashed into a fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska

July 16, 1942, Flight Sergeant (Pilot) Gordon Douglas Russel Baird became lost in a relocation mission, died at sea.

July 16, 1942, Squadron Leader (Pilot) John William Kerwin crashed into fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska.

July 16, 1942, Flight Sergeant (Pilot) Frank "Pop" Lennon crashed into fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska

July 16, 1942, Sergeant (Pilot) Stanley Ray Maxmen crashed into a fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska.

July 16, 1942, Pilot Officer (Pilot) Dean Edward "Whitey" Whiteside crashed into a fog-obscured mountain, Unalaska Island, Alaska

July 16, 1942, Flight Sergeant (Pilot) Gordon Douglas Russel Baird became lost in a relocation mission, died at sea.

July 16, 1942 was a profoundly tragic day for 111 Squadron. Five pilots and seven planes were lost in one mission. The squadron had been ordered to leave Elmendorf and make their way to Umnak Island in the Aleutian chain.

Here is the drama of those few days as recorded in the Squadron Daily Diary:

"July 13, 1942 Local flying and some formation carried out, and some instrument flying. W/C McGregor and six pilots left Elmendorf enroute to Umnak and Cold Bay, On the way to Umnak Flt/Sgt Schwalm was forced to bail out due to failure of the entire electrical system. On arrival at Naknak P/O Lynch crashed on landing. W/C McGregor and S/L Kerwin took off from Naknak to search. They were unsuccessful, but a DC3 Transport piloted by Captain Fillmore, U.S.A. Air Corps sighted Schwalm and on landing at Naknak returned with emergency rations, maps, and first aid kit. Two D.C. 3 Transports left at the same time as our flying pilots, transporting seven pilots and twenty-six men. An advance party consisted of F/O Cowan, the Medical Officer, F/O Paynter and eleven men left at 08:30 hours for Cold Bay, enroute to Umnak, arriving Cold Bay at 13:00 hours.

July 14, 1942 The advance party departed Cold Bay for Umnak at 13:00 hours, but were unable to get through due to weather conditions. W/C McGregor returned to Elmendorf to collect two more pilots and aircraft and to find out what was being done regarding F/Sgt Schwalm. In the meantime, the "Alaska Star Airlines" had picked Schwalm up at Lake Iliana. W/C McGregor returned to Umnak with P/O Eskil and F/Sgt Baird arriving at 17:40 hours.

July 15, 1942 Weather bad today. Pilots unable to leave Naknak. Good sample of camp life eating everything off one plate and using a wooden spoon.

July 16, 1942 W/C McGregor and six pilots left Naknak today for Cold Bay at 10:00 hours, accompanied by the two Transports, arriving at Cold Bay at 12:00 hours. At 13:30 hours one of the Transports piloted by Captain Fillmore left Cold Bay for Umnak. Weather was reported as suitable for the flight. At 14:00 hours, seven of our Kittyhawks took off for Umnak. Shortly after passing Dutch Harbor, the aircraft ran into bad weather. Fog was in front, behind and on the starboard side. The Wing Commander gave the order to turn back but owing to the low ceiling (50 feet), the others lost him in the turn and went into the fog. W/C McGregor landed at Cold Bay and one aircraft piloted by P/O Eskil arrived at Umnak. Apparently the remaining five had been lost. Two Transports and nine pilots, one Medical Officer, and seventeen men arrived at Umnak. Radio communications between Transports and P40's was very poor. The Wing Commander made an attempt to locate the missing aircraft and pilots in a P.B.Y., but to no avail, owing to hopeless weather conditions...

July 17, 1942 Two of our P40's were located in the morning on a hillside on Unalaska Island. A search party left by boat from Umnak, located the aircraft , and identified P/O Dean Edward "Whitey" Whiteside and F/Sgt Frank "Pop" Lennon. The bodies were brought back to Umnak. W/C McGregor arrived at Umnak."

Two others, Sergeant Pilot Stan Maxmen and Squadron Leader John William Kerwin, had also slammed into the mountain in the fog. Flight Sergeant Gordon Douglas Russell "Gordie" Baird became disoriented and probably flew until he ran out of fuel, crashing into the sea. He was never seen again.

Five pilots and seven aircraft lost in a relocation mission.

The Daily Diary version of the tragedy is terse and maddeningly without detail. What we do get is that the weather conditions were terrible and that communication was difficult, both within the formation and with ground and other support aircraft in the area. It is hard to imagine just how isolated a pilot is under such conditions and how vulnerable.

We have two witness accounts of the doomed flight. One from Squadron Leader McGregor who led the formation and the other from then-Pilot Officer Eskil, the only one who reached the intended destination that day. The two accounts were in substantial agreement as to what happened. P/O Eskil's account is richer in the details that can help us get a feel for the mission. Here is an excerpt from his very thorough and full report:

"After rounding Makushin Cape (Unalaska Island) and altering course to roughly follow the shoreline - weather became progressively worse. Fog banks and showers continually appeared to the north. We flew through several areas about 50 feet above the water. I could hear F/L Kerwin talking to Captain Fillmore (in an American C-53 support aircraft) intermittently but they seemed to be making very poor radio contact. I could not tune either one clearly.... The air seemed clear near the water but visibility was very poor - much impeded by large areas of dense fog and showers. We were forced very near the water.

... we were forced right along the shore by a dense fogbank about 200 yards offshore. We were forced to about 20 feet from the water and I estimate the ceiling at about 50 feet. We were flying with the Wing Commander leading a "VIC" consisting of F/L Kerwin's section (with Maxmen) and Pilot Officer Whiteside's section (with Lennon) on the starboard of the Wing Commander, and my section (with Baird) off the port. Sections were about three to four spans apart and ships in the sections slightly closer. F/Sgt Baird had overtaken me and slid over abruptly, forcing me to pass through his slipstream. We were very low and I dropped back slightly while righting my ship. As I was moving up to form on F/Sgt Baird's port wing, the Wing Commander ordered a turn to port. I was trailing the Wing Commander and Baird by 100 yards when the turn began. I was too low to drop into proper position for a turn and thus lost sight of all the other ships when I began my turn. I turned as tight and as low as I dared but sighted an aircraft well ahead of me cutting me off. Afraid that I would fly into the green beneath me continuing my turn and increasing throttle to about 37 Hg. My gyro horizon was out so I had trouble in maintaining steep climb and turn. At about 500 feet freezing mist appeared on my windscreen so I undid my harness and removed my oxygen and radio connections - intending to bail out if I stopped gaining height because of icing. At 4800 ft I broke through between cloud layers, continued to turn and plugged in my radio... (After being momentarily disoriented by cloud and fog and making a couple of course adjustments) In a few minutes I ended up in what turned out to be the only hole in the area and sighted the Umnak air base... I phoned Captain Fillmore to clear me so I would not be fired on and proceeded to land..."

By the time P/O Eskil was plugging in his radio, four of his fellow pilots were dead. And one was probably flying in circles. Sgt Baird wouldn't have known his fate until his fuel ran out. He must not have heard McGregor, or Fillmore or Eskil calling for him. He might have heard McGregor's order to the formation to turn left. He was turning left when he crossed in front of Eskil. If so, that was his last connection with his squadron.

Here is the drama of those few days as recorded in the Squadron Daily Diary:

"July 13, 1942 Local flying and some formation carried out, and some instrument flying. W/C McGregor and six pilots left Elmendorf enroute to Umnak and Cold Bay, On the way to Umnak Flt/Sgt Schwalm was forced to bail out due to failure of the entire electrical system. On arrival at Naknak P/O Lynch crashed on landing. W/C McGregor and S/L Kerwin took off from Naknak to search. They were unsuccessful, but a DC3 Transport piloted by Captain Fillmore, U.S.A. Air Corps sighted Schwalm and on landing at Naknak returned with emergency rations, maps, and first aid kit. Two D.C. 3 Transports left at the same time as our flying pilots, transporting seven pilots and twenty-six men. An advance party consisted of F/O Cowan, the Medical Officer, F/O Paynter and eleven men left at 08:30 hours for Cold Bay, enroute to Umnak, arriving Cold Bay at 13:00 hours.

July 14, 1942 The advance party departed Cold Bay for Umnak at 13:00 hours, but were unable to get through due to weather conditions. W/C McGregor returned to Elmendorf to collect two more pilots and aircraft and to find out what was being done regarding F/Sgt Schwalm. In the meantime, the "Alaska Star Airlines" had picked Schwalm up at Lake Iliana. W/C McGregor returned to Umnak with P/O Eskil and F/Sgt Baird arriving at 17:40 hours.

July 15, 1942 Weather bad today. Pilots unable to leave Naknak. Good sample of camp life eating everything off one plate and using a wooden spoon.

July 16, 1942 W/C McGregor and six pilots left Naknak today for Cold Bay at 10:00 hours, accompanied by the two Transports, arriving at Cold Bay at 12:00 hours. At 13:30 hours one of the Transports piloted by Captain Fillmore left Cold Bay for Umnak. Weather was reported as suitable for the flight. At 14:00 hours, seven of our Kittyhawks took off for Umnak. Shortly after passing Dutch Harbor, the aircraft ran into bad weather. Fog was in front, behind and on the starboard side. The Wing Commander gave the order to turn back but owing to the low ceiling (50 feet), the others lost him in the turn and went into the fog. W/C McGregor landed at Cold Bay and one aircraft piloted by P/O Eskil arrived at Umnak. Apparently the remaining five had been lost. Two Transports and nine pilots, one Medical Officer, and seventeen men arrived at Umnak. Radio communications between Transports and P40's was very poor. The Wing Commander made an attempt to locate the missing aircraft and pilots in a P.B.Y., but to no avail, owing to hopeless weather conditions...

July 17, 1942 Two of our P40's were located in the morning on a hillside on Unalaska Island. A search party left by boat from Umnak, located the aircraft , and identified P/O Dean Edward "Whitey" Whiteside and F/Sgt Frank "Pop" Lennon. The bodies were brought back to Umnak. W/C McGregor arrived at Umnak."

Two others, Sergeant Pilot Stan Maxmen and Squadron Leader John William Kerwin, had also slammed into the mountain in the fog. Flight Sergeant Gordon Douglas Russell "Gordie" Baird became disoriented and probably flew until he ran out of fuel, crashing into the sea. He was never seen again.

Five pilots and seven aircraft lost in a relocation mission.

The Daily Diary version of the tragedy is terse and maddeningly without detail. What we do get is that the weather conditions were terrible and that communication was difficult, both within the formation and with ground and other support aircraft in the area. It is hard to imagine just how isolated a pilot is under such conditions and how vulnerable.

We have two witness accounts of the doomed flight. One from Squadron Leader McGregor who led the formation and the other from then-Pilot Officer Eskil, the only one who reached the intended destination that day. The two accounts were in substantial agreement as to what happened. P/O Eskil's account is richer in the details that can help us get a feel for the mission. Here is an excerpt from his very thorough and full report:

"After rounding Makushin Cape (Unalaska Island) and altering course to roughly follow the shoreline - weather became progressively worse. Fog banks and showers continually appeared to the north. We flew through several areas about 50 feet above the water. I could hear F/L Kerwin talking to Captain Fillmore (in an American C-53 support aircraft) intermittently but they seemed to be making very poor radio contact. I could not tune either one clearly.... The air seemed clear near the water but visibility was very poor - much impeded by large areas of dense fog and showers. We were forced very near the water.

... we were forced right along the shore by a dense fogbank about 200 yards offshore. We were forced to about 20 feet from the water and I estimate the ceiling at about 50 feet. We were flying with the Wing Commander leading a "VIC" consisting of F/L Kerwin's section (with Maxmen) and Pilot Officer Whiteside's section (with Lennon) on the starboard of the Wing Commander, and my section (with Baird) off the port. Sections were about three to four spans apart and ships in the sections slightly closer. F/Sgt Baird had overtaken me and slid over abruptly, forcing me to pass through his slipstream. We were very low and I dropped back slightly while righting my ship. As I was moving up to form on F/Sgt Baird's port wing, the Wing Commander ordered a turn to port. I was trailing the Wing Commander and Baird by 100 yards when the turn began. I was too low to drop into proper position for a turn and thus lost sight of all the other ships when I began my turn. I turned as tight and as low as I dared but sighted an aircraft well ahead of me cutting me off. Afraid that I would fly into the green beneath me continuing my turn and increasing throttle to about 37 Hg. My gyro horizon was out so I had trouble in maintaining steep climb and turn. At about 500 feet freezing mist appeared on my windscreen so I undid my harness and removed my oxygen and radio connections - intending to bail out if I stopped gaining height because of icing. At 4800 ft I broke through between cloud layers, continued to turn and plugged in my radio... (After being momentarily disoriented by cloud and fog and making a couple of course adjustments) In a few minutes I ended up in what turned out to be the only hole in the area and sighted the Umnak air base... I phoned Captain Fillmore to clear me so I would not be fired on and proceeded to land..."

By the time P/O Eskil was plugging in his radio, four of his fellow pilots were dead. And one was probably flying in circles. Sgt Baird wouldn't have known his fate until his fuel ran out. He must not have heard McGregor, or Fillmore or Eskil calling for him. He might have heard McGregor's order to the formation to turn left. He was turning left when he crossed in front of Eskil. If so, that was his last connection with his squadron.

This painting of the Kittyhawks was created by Steve Tournay to salute the lost pilots who were involved in this tragic event. (Permission to use the picture has been granted by the artist. Thank you, Steve.)

Here are Steve Tournay's comments about this picture:

"111 and the Enemy Ace - by Steve Tournay A five-plane flight of 111 Squadron P-40 Kittyhawks flying into fog over Unalaska Island during their Aleutian detachment; all five subsequently crashed on a hillside on Unalaska. (I have very recently learned that AL138, the second Kittyhawk from the viewer's position, was recovered from Unalaska and is stored pending eventual restoration)."

In fact, it was a seven-plane flight from which four pilots flew into the mountain on Unalaska Island. The fifth became disoriented and, while he did miss the mountain, he became lost in the fog and probably crashed into the sea when he ran out of fuel. In any case, he was never heard from again.

Tournay's reference to "Enemy Ace' in the painting's title derives from the definition of Ace. The term stems from WW1 aerial conflict. A pilot earned the title Ace when he had destroyed, in aerial combat, five enemy aircraft. Tournay's use of the term salutes the weather as the greater threat to flyers in the Aleutians. In this one incident, five aircraft and their pilots were brought down by the more dangerous enemy: the weather itself.

Click here to see more of Steve's work and that of many other superb Canadian artists who specialize in aeronautical art.

Here are Steve Tournay's comments about this picture:

"111 and the Enemy Ace - by Steve Tournay A five-plane flight of 111 Squadron P-40 Kittyhawks flying into fog over Unalaska Island during their Aleutian detachment; all five subsequently crashed on a hillside on Unalaska. (I have very recently learned that AL138, the second Kittyhawk from the viewer's position, was recovered from Unalaska and is stored pending eventual restoration)."

In fact, it was a seven-plane flight from which four pilots flew into the mountain on Unalaska Island. The fifth became disoriented and, while he did miss the mountain, he became lost in the fog and probably crashed into the sea when he ran out of fuel. In any case, he was never heard from again.

Tournay's reference to "Enemy Ace' in the painting's title derives from the definition of Ace. The term stems from WW1 aerial conflict. A pilot earned the title Ace when he had destroyed, in aerial combat, five enemy aircraft. Tournay's use of the term salutes the weather as the greater threat to flyers in the Aleutians. In this one incident, five aircraft and their pilots were brought down by the more dangerous enemy: the weather itself.

Click here to see more of Steve's work and that of many other superb Canadian artists who specialize in aeronautical art.

Photo by Jeff Dickrell

This photograph tells the whole story of flying into the mountain on Unalaska Island. The man, a friend of photographer Jeff Dickrell, is sitting beside the engine of one of the 111 Squadron's P-40s, I believe it was part of the plane flown by Sergeant (Pilot) Maxmen. Judging from the angle of the engine (and allowing for 70 years of erosion and tampering) it appears that the pilot was desperately trying to pull up. He did not have enough time. Straight behind the aircraft was Dutch Harbor. They had passed over it but, never having been over Unalaska Island, they did not know about the very high sloping mountain until it suddenly loomed out of the fog. The Daily Diary said that the ceiling was 50 feet above sea level. The tallest mountain on Unalaska is about 6,000 feet high. They never had a chance.

But apparently it was a near thing.

Armourer Max Crandall recounted his experience. He was part of a search party who went up the mountain on Unalaska Island a few days later when the weather had cleared somewhat. After lunch, "we proceeded to walk up the grassy slope of this volcanic island. The grass was high, thick and wet and the moisture in the air began to penetrate our sheepskin jackets. We walked right up into the clouds..." They searched for five hours fruitlessly. "... when a little break occurred in the clouds , and myself and three others were face to face with the remnants of an aircraft scattered over a large area of the mountainside. ... The plane had hit the mountain about fifty feet below the crest; pieces of aircraft flew every which way down the mountain, and the pilot, Gordon Maxmen, had rolled down and lay alongside part of the fuselage. Chocolate bars and small personal items were scattered nearby. Now we knew that the others couldn't be far away, so we went over the ridge and here we found the remains of the other three planes. They had been flying in formation and had hit just a few feet, probably less than five, from the ridge crest and had somersaulted over the top." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 34)

In fact, Flight Sergeant Maxmen's first name was Stanley Ray, not Gordon; Max Crandall also made a mistake about the name of another of the victims in this tragic event but his memory for detail seemed pretty clear and perhaps indelible, in his mind, when describing what they actually saw.

In Alaska, there were three other deaths of men who had been associated with 111 Squadron:

June 14, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Dufferin Wilfred Wakeling died in service with 14 Squadron

March 26, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Ian MacMillan Dowling died riding in a plane downed by weather

March 28, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Arthur Jarred was killed when his bomb-equipped P-40 collapsed in an ill-advised upward roll

But apparently it was a near thing.

Armourer Max Crandall recounted his experience. He was part of a search party who went up the mountain on Unalaska Island a few days later when the weather had cleared somewhat. After lunch, "we proceeded to walk up the grassy slope of this volcanic island. The grass was high, thick and wet and the moisture in the air began to penetrate our sheepskin jackets. We walked right up into the clouds..." They searched for five hours fruitlessly. "... when a little break occurred in the clouds , and myself and three others were face to face with the remnants of an aircraft scattered over a large area of the mountainside. ... The plane had hit the mountain about fifty feet below the crest; pieces of aircraft flew every which way down the mountain, and the pilot, Gordon Maxmen, had rolled down and lay alongside part of the fuselage. Chocolate bars and small personal items were scattered nearby. Now we knew that the others couldn't be far away, so we went over the ridge and here we found the remains of the other three planes. They had been flying in formation and had hit just a few feet, probably less than five, from the ridge crest and had somersaulted over the top." (Farm Boy Goes to War, page 34)

In fact, Flight Sergeant Maxmen's first name was Stanley Ray, not Gordon; Max Crandall also made a mistake about the name of another of the victims in this tragic event but his memory for detail seemed pretty clear and perhaps indelible, in his mind, when describing what they actually saw.

In Alaska, there were three other deaths of men who had been associated with 111 Squadron:

June 14, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Dufferin Wilfred Wakeling died in service with 14 Squadron

March 26, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Ian MacMillan Dowling died riding in a plane downed by weather

March 28, 1943, Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Arthur Jarred was killed when his bomb-equipped P-40 collapsed in an ill-advised upward roll

Of course, Sergeant Pilot Baird has no grave marker. However, his name is inscribed on the Ottawa War Memorial, Ottawa, Ontario.

On December 8, 2013, I received this e-mail from Peter Schoor, great nephew of Stanley Ray Maxmen:

"In 2009 I drove to Alaska before my grandma passed (she never saw her brothers resting place when he passed) and got a pass to visit the graveyard on the Army base in Anchorage. I received a plot plan and dug my way through and have pictures of where 111 squadron were laid to rest. I have quite a few pictures of Uncle Stanley's Head Stone. After reviewing your site and talking with my grandpa, I was wondering if you would be interested in a copy of the pictures. Thank you for your time and effort devoted to the memory of so many families' lost loved ones."

Yes, Peter, this website is very interested in sharing your pictures. Your act of going to such a remote gravesite is not something everyone can do and will be inspiring to people who would like to do more to honour those who have served in our behalf. Thanks for sharing. Here are some of Peter's pictures:

On December 8, 2013, I received this e-mail from Peter Schoor, great nephew of Stanley Ray Maxmen:

"In 2009 I drove to Alaska before my grandma passed (she never saw her brothers resting place when he passed) and got a pass to visit the graveyard on the Army base in Anchorage. I received a plot plan and dug my way through and have pictures of where 111 squadron were laid to rest. I have quite a few pictures of Uncle Stanley's Head Stone. After reviewing your site and talking with my grandpa, I was wondering if you would be interested in a copy of the pictures. Thank you for your time and effort devoted to the memory of so many families' lost loved ones."

Yes, Peter, this website is very interested in sharing your pictures. Your act of going to such a remote gravesite is not something everyone can do and will be inspiring to people who would like to do more to honour those who have served in our behalf. Thanks for sharing. Here are some of Peter's pictures:

There are four members of 111 Squadron buried in this small cemetery: S/L John William Kerwin, P/O Dean Edward Whiteside, F/S Stanley Ray Maxmen and F/S Frank Robert Lennon. Their grave markers are shown above. Also buried there is F/L Dufferin Nelson Wakeling who was attached to 14 Squadron but had a temporary attachment to 111 Squadron. They lie with other servicemen who died in service in Alaska.

At the end of the Aleutian mission, 111 Squadron was redeployed to Europe to be part of the final push to finish the war there. They were renumbered as 440 Squadron because the Royal Air Force had a 111 Squadron and having two 111 Squadrons in the same theatre of war would have been too confusing. Many of the 111 Squadron pilots went to Europe but not all flew with 440 Squadron.

I am grateful to Hugh A. Halliday for publishing a quote by 111 Squadron's F/O Brian Clacken who said in a letter dated December 1, 1977: "To the best of my recollection (aided by logbook and photo album), of the 21 pilots of 111 Squadron who formed the nucleus of 440 Squadron in March, 1944, 16 had been killed by November, 1944." (Halliday, Hugh A., Typhoon and Tempest: The Canadian Story Toronto: Canav Press, p.170)

Here is a list of names of pilots who had been associated with 111 Squadron and who died in the line of duty:

October 6, 1942 Flying Officer/ Pilot Gerald Pringle Johnson collided in his first operational scramble.

November 19, 1943 Pilot Officer/ Pilot Edwin Alexander "Ed" Merkley collided in England while training in formation flying

December 21, 1943 Flying Officer/ Pilot Archibald Earle Clarke downed by flak over Cambrai, France

May 4, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot William Dempsey Peacock struck a barrage balloon cable in England

May 27, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot Nicholas Stusiak crashed in England while practising low level dog-fighting

June 7, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Stanley Vincent Garside, on a Ramrod operation, was killed by flak

June 12, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot James Gohl crashed in the English Channel after a bombing run in France

July 13, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Arnold Walter Roseland killed while on armed reconnaissance over France

July 30, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot John William Lippert failed to return from a raid near Bretteville, France.

August 1, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot William Ronald Campbell downed by flak over Caen, France

August 1, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Odin John Eskil died in a mid-air collision over Calvados, France

August 8, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Clifford Hicks was killed by ack ack fire over Normandy

August 12, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot John Fraser Dewar exploded on a dive-bombing run in France

August 12, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot George Talbot Schwalm was killed by ack ack over France

September 28, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot George Glenn Millar crashed while returning from a patrol over Holland

October 7, 1944 Squadron Leader/ Pilot William Harry Pentland exploded in a dive-bombing run in Germany

October 20, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot Ronald William Doidge shot down while dive-bombing in Holland

October 22, 1944 Squadron Leader/ Pilot Kenneth Arthur Boomer was killed over Munich, Germany

October 28, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot George Arnold Costello captured and murdered near Hennewig, Germany

November 11, 1944 Pilot Officer/ Pilot Francis Joseph Crowley was downed by flak over Holland

January 1, 1945 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot James Basil "Joe" Doak was killed over Northern Germany

January 22, 1945 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Frank Richard Fisher Skelly exploded in a dive-bombing run in Holland

I am grateful to Hugh A. Halliday for publishing a quote by 111 Squadron's F/O Brian Clacken who said in a letter dated December 1, 1977: "To the best of my recollection (aided by logbook and photo album), of the 21 pilots of 111 Squadron who formed the nucleus of 440 Squadron in March, 1944, 16 had been killed by November, 1944." (Halliday, Hugh A., Typhoon and Tempest: The Canadian Story Toronto: Canav Press, p.170)

Here is a list of names of pilots who had been associated with 111 Squadron and who died in the line of duty:

October 6, 1942 Flying Officer/ Pilot Gerald Pringle Johnson collided in his first operational scramble.

November 19, 1943 Pilot Officer/ Pilot Edwin Alexander "Ed" Merkley collided in England while training in formation flying

December 21, 1943 Flying Officer/ Pilot Archibald Earle Clarke downed by flak over Cambrai, France

May 4, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot William Dempsey Peacock struck a barrage balloon cable in England

May 27, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot Nicholas Stusiak crashed in England while practising low level dog-fighting

June 7, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Stanley Vincent Garside, on a Ramrod operation, was killed by flak

June 12, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot James Gohl crashed in the English Channel after a bombing run in France

July 13, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Arnold Walter Roseland killed while on armed reconnaissance over France

July 30, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot John William Lippert failed to return from a raid near Bretteville, France.

August 1, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot William Ronald Campbell downed by flak over Caen, France

August 1, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Odin John Eskil died in a mid-air collision over Calvados, France

August 8, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Clifford Hicks was killed by ack ack fire over Normandy

August 12, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot John Fraser Dewar exploded on a dive-bombing run in France

August 12, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot George Talbot Schwalm was killed by ack ack over France

September 28, 1944 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot George Glenn Millar crashed while returning from a patrol over Holland

October 7, 1944 Squadron Leader/ Pilot William Harry Pentland exploded in a dive-bombing run in Germany

October 20, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot Ronald William Doidge shot down while dive-bombing in Holland

October 22, 1944 Squadron Leader/ Pilot Kenneth Arthur Boomer was killed over Munich, Germany

October 28, 1944 Flying Officer/ Pilot George Arnold Costello captured and murdered near Hennewig, Germany

November 11, 1944 Pilot Officer/ Pilot Francis Joseph Crowley was downed by flak over Holland

January 1, 1945 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot James Basil "Joe" Doak was killed over Northern Germany

January 22, 1945 Flight Lieutenant/ Pilot Frank Richard Fisher Skelly exploded in a dive-bombing run in Holland

F/O (Pilot) John William Lippert F/L (Pilot) George Glenn Millar F/L (Pilot) Odin John Eskil

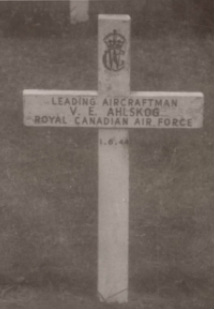

One former 111 Ground Crew member also died in service:

June 1, 1944 Leading Aircraftman Victor Edward Ahlskog died when a 418 Squadron Mosquito he was riding in crashed in England.

June 1, 1944 Leading Aircraftman Victor Edward Ahlskog died when a 418 Squadron Mosquito he was riding in crashed in England.

A Funeral with Full Military Honours

Photographs showing the Funeral of 440 Squadron's Flying Officer (Pilot) Nicholas Stusiak, who died May 27, 1944 in a dogfight training accident near Bransgrove Village, Christchurch, England. He was flying a Hawker Typhoon. The burial was in North Cemetery, Bournemouth, Hampshire, England. F/O Stusiak had been a member of 111 Squadron and served in Alaska before going to Europe with 440 Squadron. (The photographs were created by RCAF personnel and come from the Stusiak Family Collection courtesy of Michael Stusiak.)

To get an overview of the types of ground based anti-aircraft weaponry the pilots faced, press here.

To put the 111 Squadron losses in proportion to the overall aircrew losses on both sides, press here.

Thanks to TSJ Inc. who compiled the statistics and did the analyses on aircrew losses and anti-aircraft weaponry.

To put the 111 Squadron losses in proportion to the overall aircrew losses on both sides, press here.

Thanks to TSJ Inc. who compiled the statistics and did the analyses on aircrew losses and anti-aircraft weaponry.

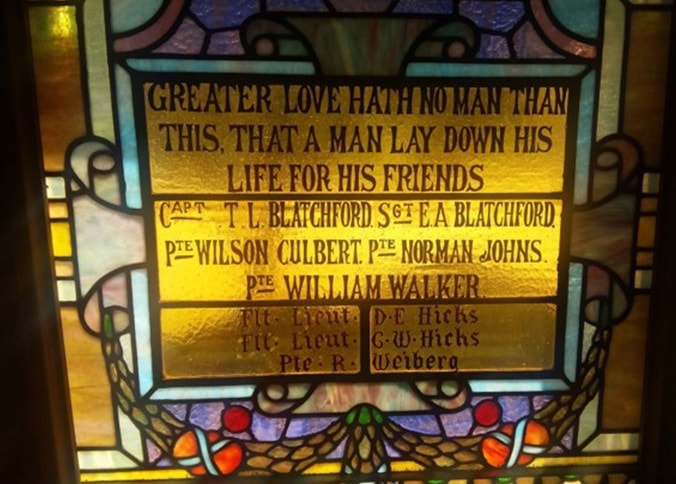

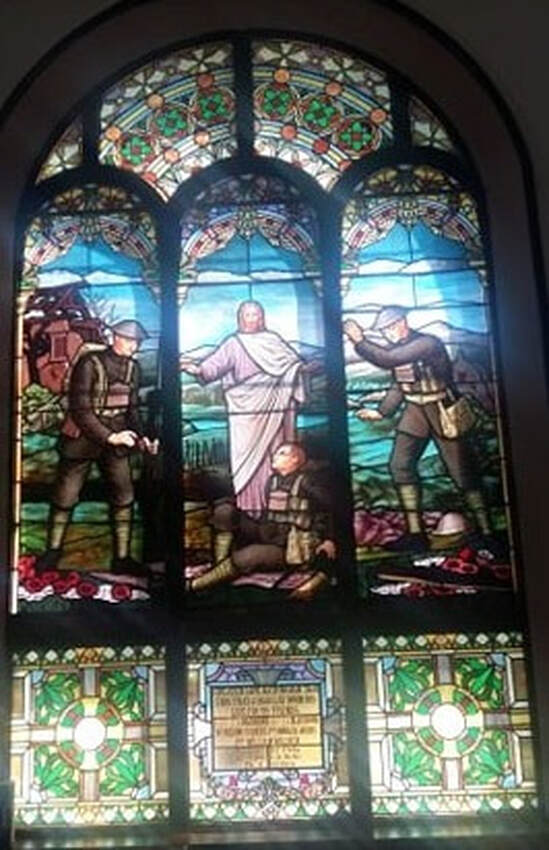

Honouring saints and heroes with stained glass has a very long tradition in churches. The United Church in Centralia, Ontario chose to preserve the memory of local WWII heroes, including Flight Lieutenant Clifford Hicks and his cousin Flight Lieutenant Donald F. HIcks.. Both were Pilots. Don flew bombers in RCAF No. 76 Squadron. Cliff flew fighters in No. 111 Squadron and later in RCAF No. 440 Squadron.

These photos were taken and sent by Jason and Rob Essery. Beautifully done guys. Thank you for letting us use them here. I am grateful to Meghan Creech , Cliff Hicks' Great Niece for confirming the relationship between Cliff and Donald.

These photos were taken and sent by Jason and Rob Essery. Beautifully done guys. Thank you for letting us use them here. I am grateful to Meghan Creech , Cliff Hicks' Great Niece for confirming the relationship between Cliff and Donald.